Page snapshot: An overview of the Mexican wolf (lobo), including what it is, why it is imperiled, what it is being done to help it recover.

Topics covered on this page: What is the Mexican wolf and why is it imperiled?; What is being done to conserve the Mexican wolf?; What are the barriers to Mexican wolf recovery?; How are institutions in Albuquerque helping the Mexican wolf?; Resources.

Credits: Funded by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Page by Elizabeth J. Hermsen (2024).

Updates: Page last updated April 15, 2024.

Image above: A Mexican wolf, Sevilleta Wolf Management Facility, New Mexico, USA. Photo by US Fish and Wildlife Service (public domain).

What is the Mexican wolf and why is it imperiled?

The Mexican wolf or lobo (Canis lupus baileyi) is a subspecies of the gray wolf (Canis lupus). Gray wolves were once found widely in North America and Eurasia. They have a smaller distribution today than they had historically, largely because people viewed wolves as nuisance predators and baited, trapped, and hunted them to extinction in some areas. In the US, wolves were even hunted and poisoned in protected areas, like Yellowstone National Park, which was first established in 1872. The last of the original Yellowstone wolves may have been killed in the 1920s.

Today, the gray wolf is missing from most of its former range in the 48 contiguous states of the United States, although it has been reintroduced or naturally reestablished itself in the northern Rocky Mountains, the Pacific Northwest, the Upper Midwest, and the Southwest. Despite the low number of wolves in the lower 48 states, wolf hunting is currently allowed in some areas.

A gray wolf at Little America Flats, Lamar Valley, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, USA. Gray wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone in the 1990s. Their presence has affected the ecology of the park and allowed researchers to observe that large predators like wolves are critical to maintaining healthy ecosystms. Photo by Jim Peaco, NPS (National Park Service, public domain).

The Mexican wolf was once found in the southwestern United States, including Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas, as well as in large parts of Mexico. As settlers moved to the southwestern US and began to raise livestock there, they saw the wolves as a problem because wolves sometimes kill livestock. Therefore, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ranchers and later the US Bureau of Biological Survey (now the US Fish and Wildlife Service) tried to eliminate all of the Mexican wolves, first killing them off in the US, then later in Mexico. Very few Mexican wolves remained by the 1970s, either in the wild or in captivity.

Mexican wolf. USDA APHIS WS (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

What is being done to conserve the Mexican wolf?

The US Endangered Species act was passed in 1973, and the gray wolf was listed as endangered in 1976. Once gray wolves were protected, plans were made to try to revive the Mexican wolf population. Between 1977 and 1980, some of the few Mexican wolves left in the wild were captured to establish a captive breeding program.

In the late 1990s, the first captive-bred Mexican wolves were released in the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, a large area spanning parts of Arizona and New Mexico, as well as a small part of western Texas. More wolves have since been released in the US and Mexico, and the total wild Mexican wolf population now numbers more than 200 wolves.

A team working on a Mexican wolf (probably doing a health check), 2019. Photo by Mexican Wolf Interagency Field Team, US Fish and Wildlife Service, public domain.

Original caption: "A Mexican wolf is released back into the wild with a radio collar." 2022. Photo by Mexican Wolf Interagency Field Team, US Fish and Wildlife Service, public domain.

What are the barriers to Mexican wolf recovery?

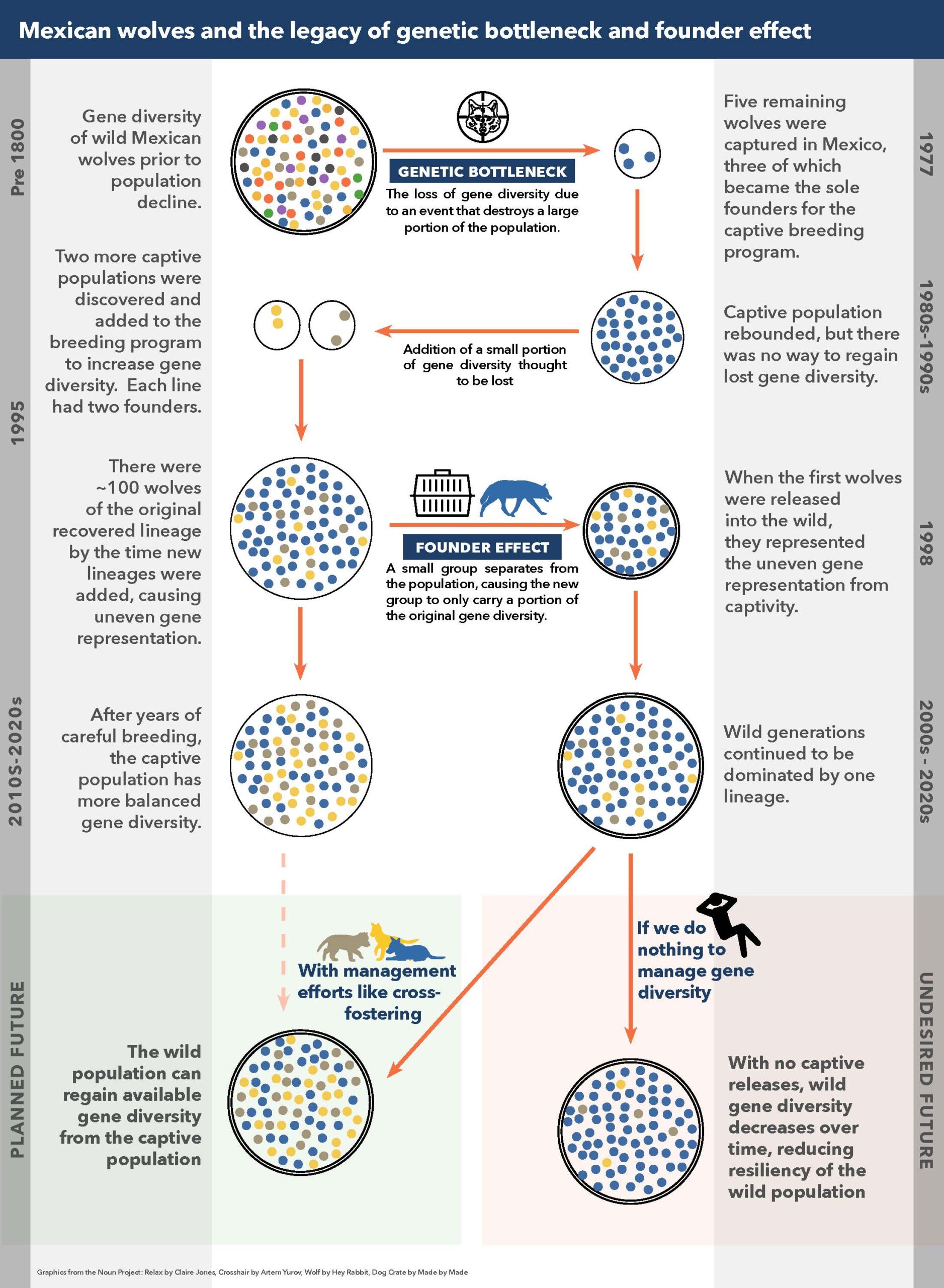

Mexican wolves face challenges, including lack of genetic diversity because all of the wolves released into the wild have descended from a small number of ancestors, a phenomenon known as the founder effect. Scientists are trying to increase the genetic diversity of Mexican wolves by cross fostering wolf pups. In cross fostering, pups born in captivity are taken by wildlife managers and placed with wild wolf packs to be raised, which promotes genetic diversity in the wild population.

Additionally, many Mexican wolves do not die natural deaths in the wild. From 1998 to 2019, the top cause of death for the wolves in the US was "illegal mortality" (more than 50% of wolves). More than 10% were also killed by being struck by vehicles.

Original caption: "Mexican wolf gene diversity has been affected by both genetic bottleneck and the founder effect. Managers can use cross-fostering to bring valuable gene diversity from the captive population into the wild population." Diagram by Naomi Blinick, US Fish and Wildlife Service, public domain.

Cross-fostered Mexican wolf pups. Mexican Wolf Interagency Field Team, USFWS, public domain.

How are institutions in Albuquerque helping the Mexican wolf?

Both the Museum of Southwestern Biology and the Albuquerque BioPark have played roles in understanding the biology of Mexican wolves and contributing to their recovery. The Museum of Southwestern Biology has by far the largest number of Mexican wolf specimens in the United States and works with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to collect samples and record detailed information about Mexican wolves today. Albuquerque BioPark has been involved in housing and rearing live wolves. In 2021, a group of Mexican wolves, including a male named Ryder, a female named Kawi, and their seven pups, was transferred from Albuquerque BioPark to a facility in Mexico, with the goal of eventually releasing them into the wild in Mexico.

Mexican wolf, Albuquerque BioPark, New Mexico, 2016. Photo by rbaire (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

Resources

Web resources

Bottlenecks and founder effects (Understanding Evolution): https://evolution.berkeley.edu/bottlenecks-and-founder-effects/

Conserving the Mexican wolf (US Fish & Wildlife Service): https://www.fws.gov/program/conserving-mexican-wolf

In boost to conservation of endangered species, ABQ BioPark's wolf pack to be released into the wild (City of Albuquerque): https://www.cabq.gov/artsculture/biopark/news/abq-bioparks-wolf-pack-to-be-released-into-the-wild

Mexican gray wolf, Canus lupus baileyi (Museum of Southwestern Biology): http://www.msb.unm.edu/divisions/mammals/the-collection/mexican-gray-wolf.html

Wolf wars: America's campaign to eradicate the wolf (PBS Nature): https://www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/the-wolf-that-changed-america-wolf-wars-americas-campaign-to-eradicate-the-wolf/4312/

Scientific articles and book chapters

Hedrick, P.W., and R.J. Fredrickson. 2008. Captive breeding and the reintroduction of Mexican and red wolves. Molecular Ecology 17: 344-350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03400.x

Heffelfinger, J.R., R.M. Nowak, and D. Paetkau. 2017. Clarifying historical range to aid recovery of the Mexican wolf. Wildlife Management 81: 766-777. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21252

Povilitis, A., D.R. Parson, M.J. Robinson, and C.D. Becker. 2006. The bureaucratically imperiled Mexican wolf. Conservation Biology 20: 942-945. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3879161