Page snapshot: A case study of how museum collections can help scientists understand emerging diseases, with a focus on the "Sin Nombre" hantavirus, a virus that caused an outbreak of respiratory disease in the Southwest in 1993.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; 1993 outbreak; Origin of the virus and the role of museum collections; The role of climate; The role of indigenous knowledge; Avoiding hantavirus; Resources.

Credits: Funded by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Page by Elizabeth J. Hermsen (2024).

Updates: Page last updated April 2, 2024.

Image above: A transmission electron micrograph (a type of image taken with a specialized microscope) of the Sin Nombre hantavirus. Photo by Cynthia Goldsmith/CDC (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Introduction

Museums hold specimens and other types of samples that are useful for understanding not only the biodiversity, evolution, and ecology of organisms, but also for understanding problems that confront humans in our ever-changing world. One of these is helping to identify previously unknown diseases, also known as emerging diseases.

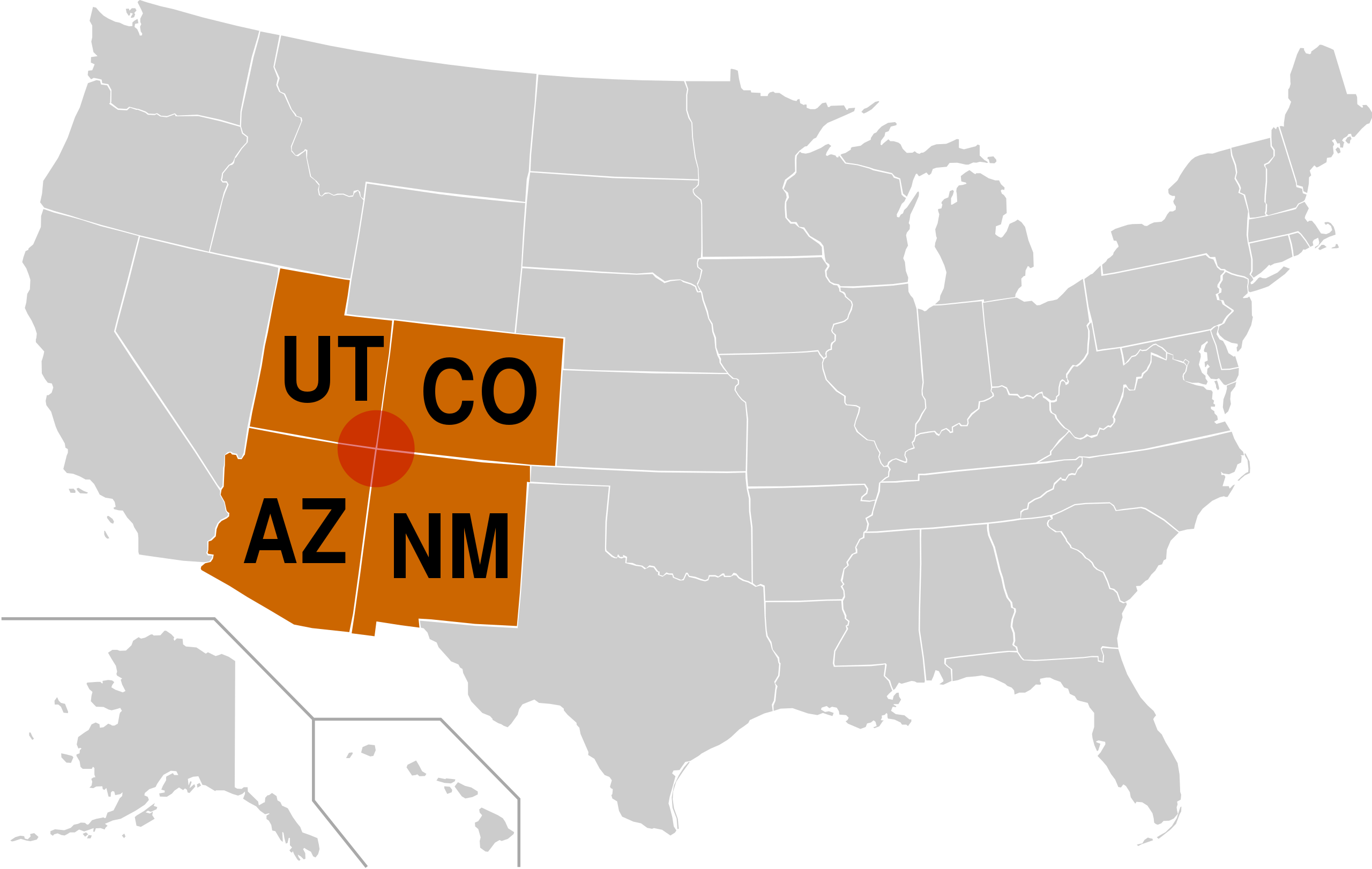

In 1993, a mysterious respiratory disease began to affect a small number of people in the Four Corners region of the southwestern USA. This disease came on suddenly and had a very high mortality rate; 70% of people who came down with the symptoms rapidly died. Researchers raced to determine the cause of the disease and figure out whether it was new to the United States. Collections held in the Museum of Southwestern Biology in Albuquerque, New Mexico, played a critical role in understanding the origin and spread of the mystery disease, now called hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS).

A map of the Four Corners region (red circle) of the southwestern U.S. The Four Corners are where Utah (UT), Colorado (CO), Arizona (AZ), and New Mexico (NM) come together. Map by Braindrain0000 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

1993 outbreak

The first cases of a mysterious new respiratory illness in the Four Corners region of the Southwest were identified by doctors and scientists in May 1993. The victims of the illness were a young, healthy New Mexico couple who died within several days of one another. More people began to come down with the illness and more cases that were previously overlooked were identified. Scientists and doctors gathered data from the patients and eliminated some possibly causes of the illness, like a chemical or the pneumonic plague. (The pneumonic plague is a respiratory form of the plague, a disease caused by a bacterium that is carried by rodents in the western US.)

One theory that researchers considered was that the illness was caused by a type of virus called a hantavirus. Hantaviruses are found in rodents in every part of the world. Only some hantaviruses can infect people, who usually contract the viruses from rodent urine, droppings, or saliva. In Europe and Asia, hantaviruses cause a group of human illnesses collectively known as hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS). HFRS affects the kidneys and other organs and causes internal bleeding, not the respiratory symptoms seen in people who had the mystery illness in the US.

Scientists at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tested tissue samples from people who had contracted the mystery illness. Based on the results, they concluded that a previously unknown hantavirus was the cause of the disease. They eventually called the virus the "Sin Nombre virus" (nameless virus), or SNV. They also trapped and tested many rodents in the Southwest and identified the main rodent host of the virus as the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus). Since 1993, more hantaviruses that can cause illness in humans have been found in North and South America.

A person studying a rodent in the field during the 1993 outbreak of hantavirus. Photo by Cheryl Tryon/CDC (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

A deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) in Portal, Arizona, 2004. Deer mice are the most important rodent carriers of hantavirus in the Southwest. Photo by Gregory Smith (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Origin of the virus and the role of museum collections

Researchers wanted to know whether the Sin Nombre hantavirus that caused the 1993 illnesses and deaths was new to the Southwest or whether it had been present there for a long time. One way to figure out whether it was new or not was to look for evidence of the virus in deer mice that lived and died in the Southwest before the 1993 outbreak. But where could investigators find mice that had lived and died in the past?

The answer was to look in museum collections. Frozen deer mice held in the Museum of Southwestern Biology in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and at Texas Tech in Lubbock, Texas, were tested for antibodies to the virus. Scientists found antibodies in more than 10% of the deer mice that they tested and discovered that the virus was present in deer mice in the Southwest at least as early as 1979.

Other evidence backed up the finding that the virus was present in the Southwest before 1993. Scientists identified some people who died of hantavirus before the 1993 outbreak. They determined that these people had had hantavirus by reviewing their medical records and by testing tissue samples from the victims that had been preserved. One man even survived a case of hantavirus in 1959! The man was hospitalized with symptoms of the virus after exposure to rodents in Colorado in the 1950s. His blood was tested for antibodies to the Sin Nombre virus in the 1990s, confirming that he had been infected.

Frozen samples at the Museum of Southwestern Biology, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo courtesy of the project PIs (all rights reserved).

Frozen samples at the Museum of Southwestern Biology, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Photo courtesy of the project PIs (all rights reserved).

The role of climate

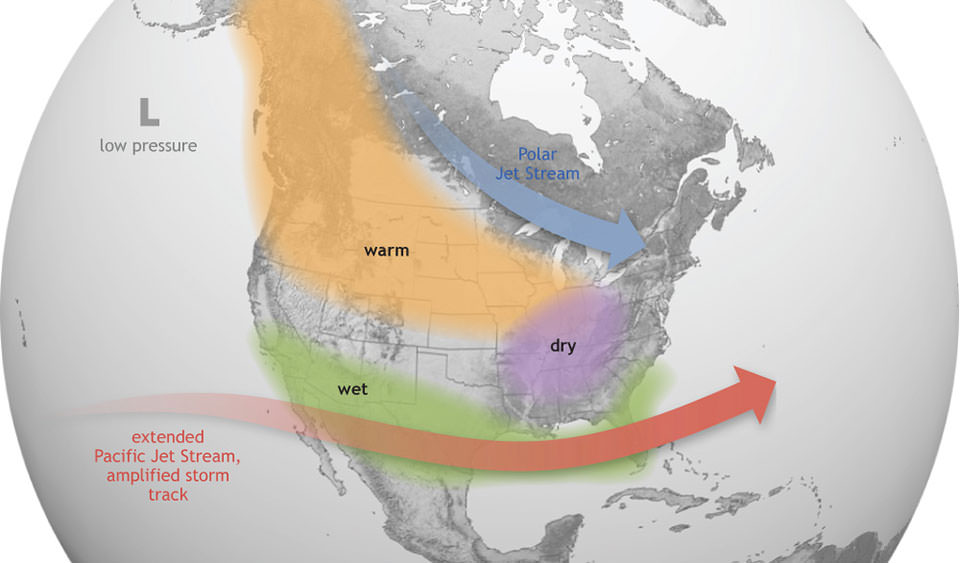

After the identity of the virus causing the mystery illness was sorted out and deer mice had been identified as the carriers, scientists began to examine the role of climate to determine whether Sin Nombre virus outbreaks are linked to fluctuating weather patterns. They found that wet years stimulated more plant growth which, after a short period of time, caused an increase in the density of the deer mouse population. For example, the year 1992 was very wet, which caused more plant growth in 1992, and a very high deer mouse population in 1993, the year of the outbreak of the Sin Nombre virus.

Scientists analyzed data from multiple years and concluded that rainy fall to spring seasons led to increases in rodent densities and higher numbers of hantavirus cases in the Southwest. Wet fall to spring seasons often occur in the Southwest during years when El Niño is active. El Niño is a climate pattern that brings increased precipitation to the Southwest. The delay between an El Niño year and a rise in hantavirus cases may be one to several years. Other factors, such as how many rodents are infected with hantavirus and whether people take steps to reduce the risk of catching hantavirus also play a role in Sin Nombre virus outbreaks.

The weather pattern during El Niño years brings increased moisture to the Southwest. Map from NOAA National Ocean Service.

A person taking a urine sample from a hantavirus-infected deer mouse, New Mexico, 2002. Photo by Hanta1. (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

The role of indigenous knowledge

The first victims of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome identified during the 1993 outbreak were members of the Navajo Nation. Navajo oral history recorded an illness associated with wet periods when many pinyon nuts (the edible seeds of the pinyon pine tree, Pinus edulis) were produced and mouse populations were high. Outbreaks of the illness had occurred in 1918 and 1933. Beyond this, Navajo traditional knowledge associates mice with disease and advises people to take practical steps to keep mice out of homes and food supplies. These details suggest that there may have been outbreaks of the Sin Nombre virus before 1993. These years were also associated with wet weather and abundant food for rodents.

Unfortunately, early media coverage of the hantavirus outbreak of 1993 was sensational and linked the virus to the Navajo people in ways that promoted discrimination. Native American people in the Four Corners region of the Southwest have been disproportionately affected by outbreaks of the Sin Nombre virus because their communities are in rural areas where infected deer mice are sometimes plentiful. Deer mice are also found in suburbs, although they are not as common in urban areas because they are displaced by other rodents.

A pinyon pine (Pinus edulis) forest near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photo by Bryan Ungard (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license).

Avoiding hantavirus

The Sin Nombre hantavirus is not found in all areas of the United States. Most cases of hantavirus occur in the western US (the US west of the Mississippi River), with New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona having the most total cases. Occasional hantavirus cases occur in the eastern USA, and some of these have been linked to different hantaviruses than the Sin Nombre virus.

The best way to avoid hantaviruses is to avoid contact with rodents, rodent urine, and rodent droppings in areas where hantaviruses occur. The four carriers of hantaviruses that have infected humans in the US are the deer mouse, the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus), and the rice rat (Oryzomys palustris). While hantaviruses can be passed from rodent to human, there are no known cases of them being passed from an infected person to another person in the US.

A hispid cotton rat (Signmodon hispidus), Florida, USA. Photo by dvollmar (iNaturalist, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

For people who live in areas where hantaviruses that can infect humans occur, it is important to keep rodents out of homes and other buildings. This means finding and sealing places where they can enter and properly storing food sources that attract rodents, like food stored in kitchens, pet food, animal feed, bird seed, and garbage. If rodents get in a building, they should be trapped and removed using proper protective equipment. Similarly, rodent urine and droppings should be cleaned using proper protection. Even vehicles should be monitored for rodent infestations.

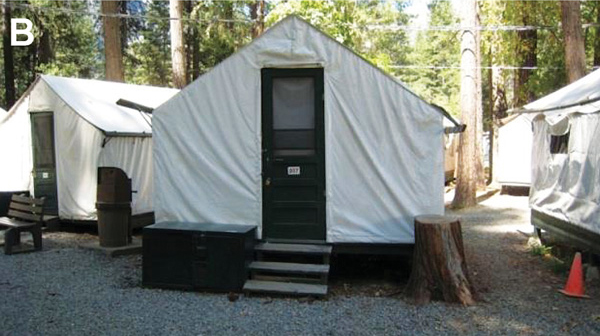

Visitors to areas were the Sin Nombre hantavirus occurs should also be aware of the risk and avoid rodents and their waste. For example, a 2012 outbreak of Sin Nombre virus in Yosemite National Park, California, infected a total of 10 park visitors and killed three of them. Investigators believe that most of the visitors contracted hantavirus while staying in tent cabins in the park. An investigation found that deer mice had been living in the cabin insulation, and about 14% of the deer mice tested had antibodies for the Sin Nombre hantavirus.

A signature tent cabin, Yosemite National Park, California, USA. A group of people who stayed in these cabins in the summer of 2012 contracted hantavirus, and three died. Fig. 2B from Núñez et al. (2014) Emerging Infectious Diseases 20 (image cropped).

Original caption: "Damage from rodents tunneling in the foam insulation of a signature tent cabin, Yosemite National Park, summer 2012." Fig. 4 from Núñez et al. (2014) Emerging Infectious Diseases 20.

Resources

Web resources

Hantavirus (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention): https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/index.html

Plague (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention): https://www.cdc.gov/plague/index.html

What are El Niño and La Niña? (NOAA National Ocean Service): https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ninonina.html

Articles

Borowski, S. 2013. The virus that rocked the Four Corners reemerges. Scientia, 8 January 2013. https://www.aaas.org/virus-rocked-four-corners-reemerges

Reid, B. 1993. Navajo doctor turned to his culture for answers. The Salt Lake Tribune, pg. D4, 2 August 1993. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6qs0h8r

Sternberg, S. 1994. Tracking a mysterious killer virus in the Southwest. The Washington Post, 14 June 1994. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/wellness/1994/06/14/tracking-a-mysterious-killer-virus-in-the-southwest/5e074ccd-7d88-41c0-9dc4-c0edcc1cd16e/

Scientific articles

Bakker, F.T., A. Antonelli, J.A. Clarke, J.A. Cook, S.V. Edwards, P.G.P. Ericson, S. Faurby, N. Ferrand, M. Gelang, R.G. Gillespie, M. Irestedt, K. Lundin, E. Larsson, P. Matos-Maravi, J. Müller, T. von Proschwitz, G.K. Roderick, A. Schliep, N. Wahlberg, J. Wiedenehoeft, and M. Källersjö. 2020. The Global Museum: natural history collections and the future of evolutionary science and public education. PeerJ 8: e8225. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8225

Dunnum, J.L., R. Yanagihara, K.M. Johnson, B. Armien, N. Batsaikhan, L. Morgan, and J.A. Cook. 2017. Biospecimen repositories and integrated databases as critical infrastructure for pathogen discovery and pathobiology research. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11: e0005133. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005133

Frampton, J.W., S. Lanser, C.R. Nichols, and P.J. Ettestad. 1995. Sin Nombre virus infection in 1959. The Lancet 346: 781-782. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91542-7

Nuñez, J.J., C.L. Fritz, B. Knust, D. Buttke, B. Enge et al. 2014. Hantavirus infections among overnight visitors to Yosemite National Park, California, USA, 2012. Emerging Infectious Diseases 20: 386-393. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2003.131581

Pottinger, R. 2005. Hantavirus in Indian Country: The first decade in review. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 29: 35-56.

Yates, T.L., J.N. Mills, C.A. Parmenter, T.G. Ksiazek, R.R. Parmenter, J.R. Vande Castle, C.H. Calisher, S.T. Nichol et al. 2002. The ecology and evolutionary history of an emergent disease: hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Bioscience 52: 989-998. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0989:TEAEHO]2.0.CO;2