Page snapshot: Quick facts about Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense), an invasive weed often considered among the most noxious in the world.

Topics covered on this page: What is Johnsongrass?; How is Johnsongrass identified?; Where did Johnsongrass come from?; How does Johnsongrass spread?; What are the impacts of Johnsongrass?; How is Johnsongrass controlled?; Resources.

Credits: Funded by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Page by Naomi Schulberg (2023).

Updates: Page last updated June 26, 2023.

Image above: Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense) inflorescence. Photo by Steve Dewey, Utah State University (Bugwood.org image 1459233, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License, image cropped).

What is Johnsongrass?

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense) is a perennial grass that grows up to 10 feet (3 meters) tall and spreads via rhizomes. Johnsongrass is considered to be an extremely serious threat to ecosystems and agriculture and is commonly listed as one of the top ten most noxious weeds in the world.

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense). Photo by Chris Evans (Bugwood.org image 2149089, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License).

How is Johnsongrass identified?

Johnsongrass is generally 3 to 10 feet (0.9 to 3 meters) tall. It has alternate leaves that measure about 12 to 30 inches long (30.5 to 76 centimeters long). Each leaf has a distinctive white midrib.

At first glance, Johnsongrass resembles maize (Zea mays) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), but, unlike either, its stems and leaves are narrow and hairless. Johnsongrass flowers are arranged in a panicle, and flowering occurs from May to October. Mature spikelets (the seed-containing structures) are small and egg shaped and range from red to black in color.

Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense). Photo by Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Mature spikelets (seed-containing structures) of Johnsongrass. Photo by Julia Scher, USDA APHIS PPQ (Bugwood.org image 5376838, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States license, image cropped and resized).

Where did Johnsongrass come from?

Johnsongrass is native to the Mediterranean region of Europe and Africa, as well as the Middle East northward and eastward into Asia. It has been widely introduced elsewhere, however, and is now found in the Americas and in areas of Africa, Europe, and Asia beyond its native range. It is well adapted to survive in a wide range of climates, from tropical to temperate, and is found in a variety of habitats. It is well suited to riparian corridors and frequently disturbed areas.

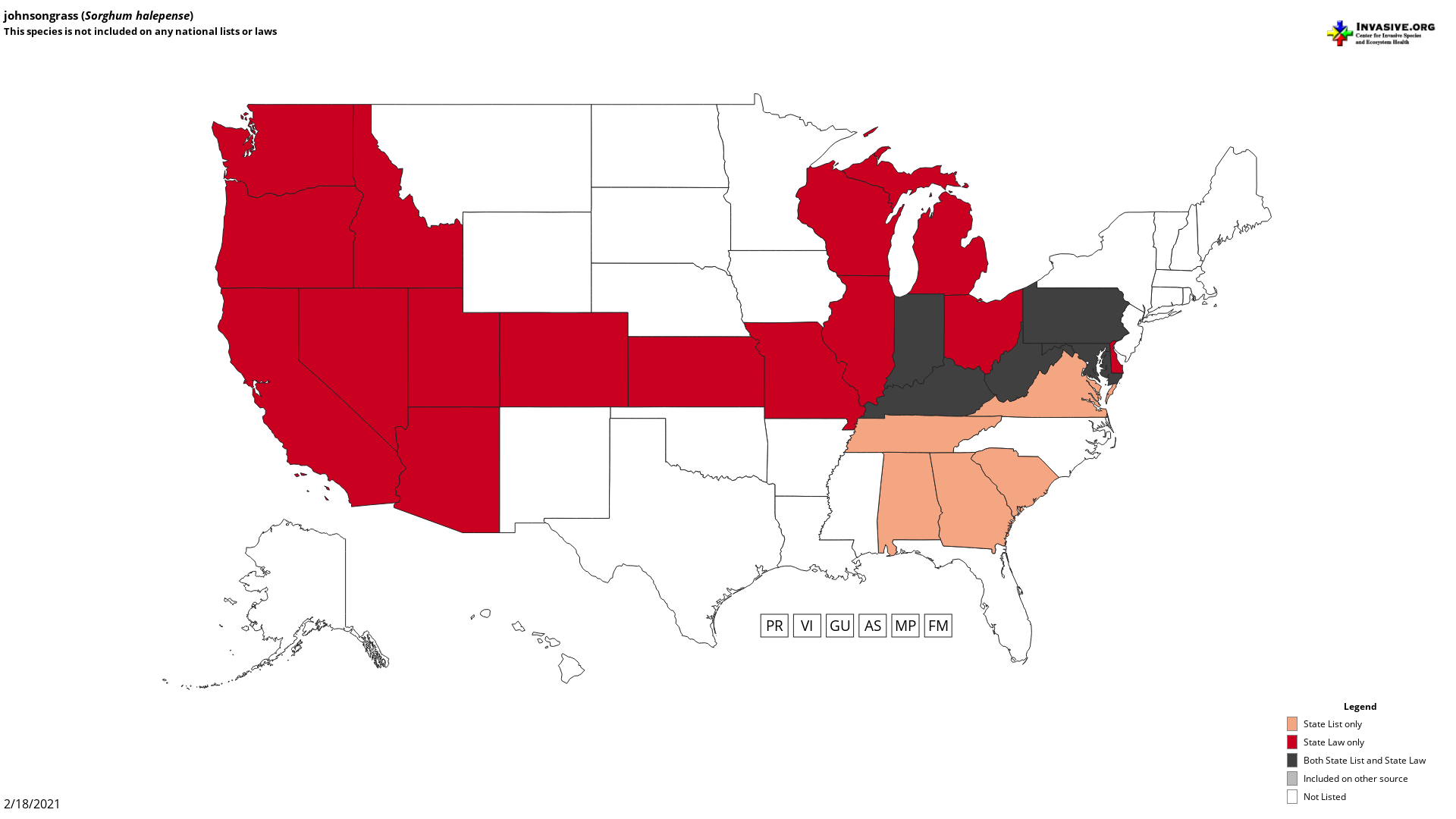

Johnsongrass was first introduced into the United States in the early 1800s from Turkey for use as a forage plant. Today, it is found in every state besides Maine, Minnesota, and Alaska.

Map of states where Johnsongrass is considered invasive. Image from EDDMapS, Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System (The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed May 30, 2023).

How does Johnsongrass spread?

Johnsongrass spreads both vegetatively and via seeds. Johnsongrass spreads vegetatively through its rhizomes. After the above-ground shoots die every fall, the underground rhizomes remain dormant. When temperatures get above around 60ºF (15.6ºC) the following year, new shoots emerge from the rhizomes. Rhizome growth is the major way that Johnsongrass spreads; in a single year, one plant may produce up to 300 feet (more than 90 meters) of rhizomes!

Johnsongrass also produces seeds during the late summer to early fall, which are dispersed by wind, water, and animals.

What are the impacts of Johnsongrass?

Due to its prolific seeding, ability to survive in a variety of conditions, and height (which allows it to shade out other plants), Johnsongrass can outcompete native plants. Like other weeds, Johnsongrass creates monocultures (in other words, areas that are dominated by only one species) as it spreads.

Johnsongrass causes a variety of problems for natural ecosystems and for agriculture. Johnsongrass can harm populations of native grasses as well as the production of important crops, including maize, sugarcane, and wheat. Johnsongrass may increase the risk of fire due to the high density of its stands. It can also produce cyanide following periods of stress (for example, following frost or cutting), which will make Johnsongrass poisonous to livestock if consumed.

How is Johnsongrass controlled?

Johnsongrass is commonly listed as among the top ten "worst weeds" in the world. One reason for its bad reputation is that it is difficult to contain its spread. In order to control Johnsongrass, a variety of management strategies are often used together. Because most growth occurs from rhizomes, many strategies focus on damaging the rhizomes. Plowing and tilling, along with herbicides, are commonly used to prevent the spread of Johnsongrass.

Planting alfalfa (Medicago sativa, a legume often used for livestock feed) alongside stands of Johnsongrass is also a way of preventing the spread of Johnsongrass. Alfalfa is one of the few plants that can compete with Johnsongrass, although only temporarily.

Johnsongrass control using herbicides. Photo by James H. Miller, USDA Forest Service (Bugwood.org number 0016368, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Resources

Websites

Species profile: Sorghum halepense (Global Invasive Species Database): http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/speciesname/Sorghum+halepense

Johnsongrass (Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences): https://cals.cornell.edu/weed-science/weed-profiles/johnsongrass