Snapshot: Introduction to the life cycle of cultivated sorghum, from planting to harvest.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; Germination and vegetative growth; Seed germination; Post-germination vegetative growth; Reproductive growth; Fruit maturation (grain filling); Resources.

Credits: Funded by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Page by Elizabeth J. Hermsen (2023), modeled on and including some text from Life cycle of maize.

Updates: Page last updated March 16, 2023.

Image above: A field of sorghum. Photo source: K-State Research and Extension on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Introduction

Domesticated sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) is grown from seed in cultivated fields, typically as an annual crop. This page will go through the growth and development of a sorghum plant cultivated for grain, from germination to harvest.

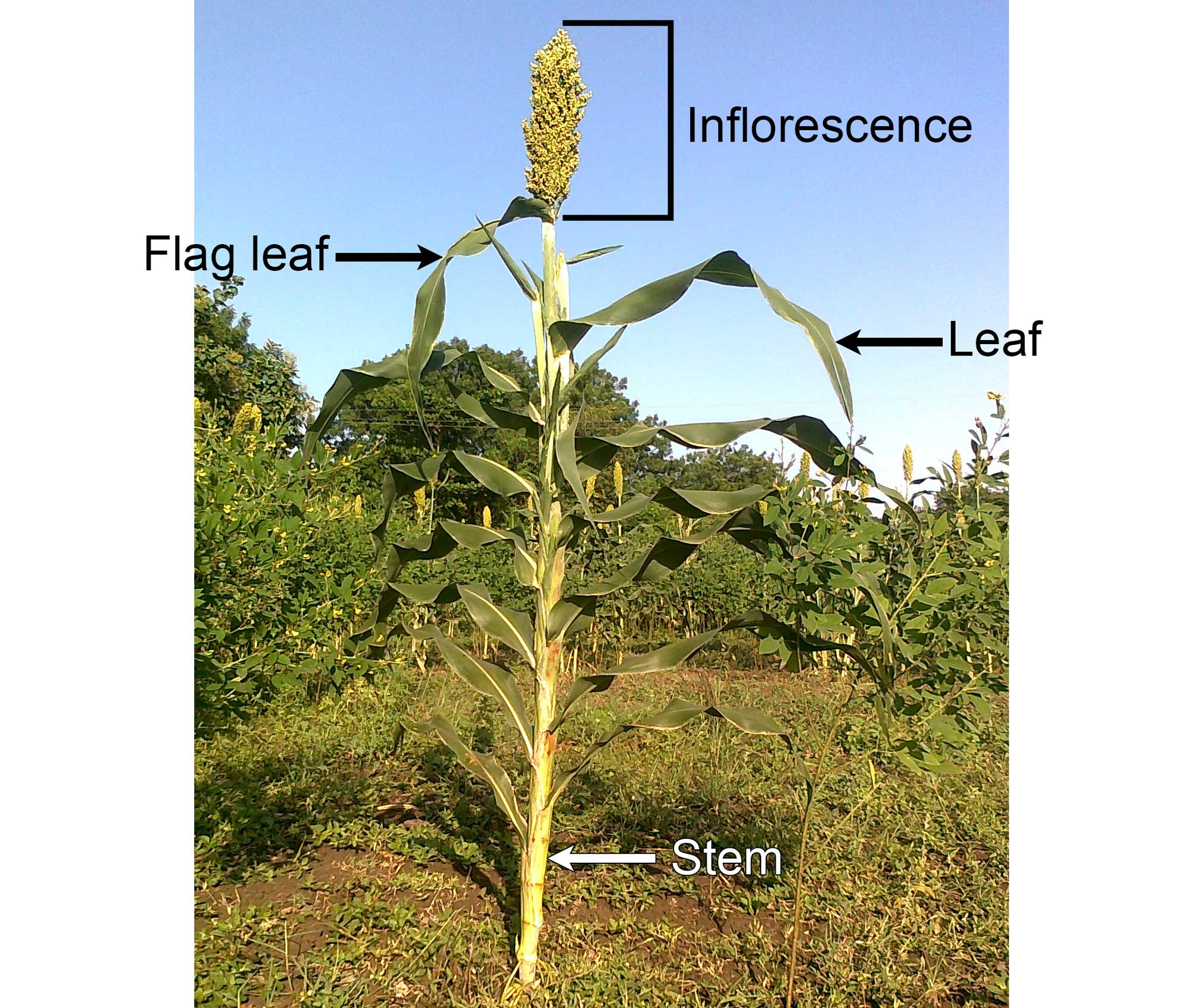

Photograph of a sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) plant, labeled. Photo by ABHIJEET (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped, resized, labeled).

Field of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), New South Wales, Australia. Photo by Harry Rose (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Germination and vegetative growth

Seed germination

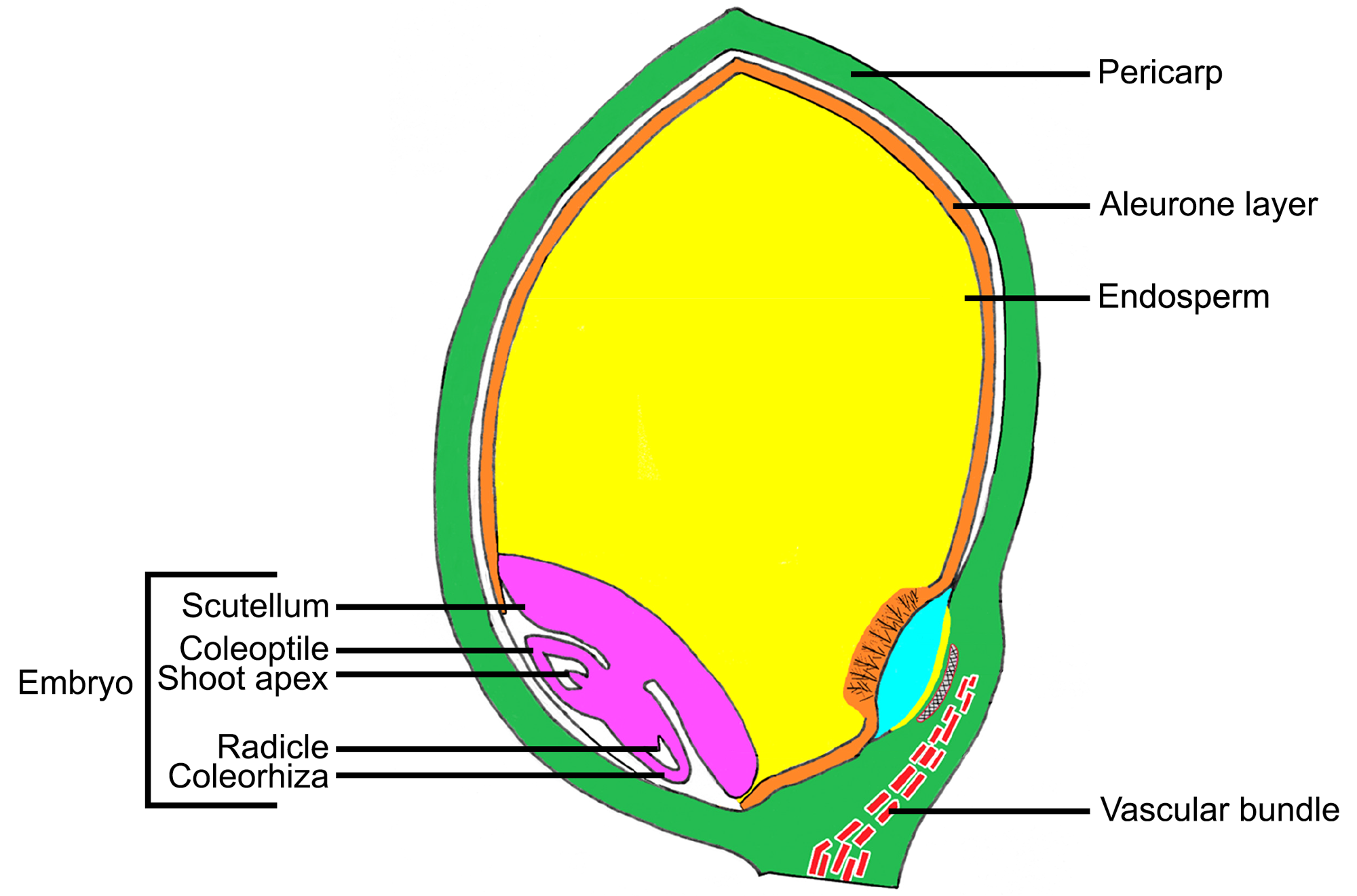

Development of the sorghum plant begins in the embryo, which uses energy stored in the endosperm to fuel its growth. Seed germination is the first step in the growth of sorghum after seeds are planted.

The radicle (primary root) grows first, splitting the seed coat. Seminal roots (roots that develop on the embryo above the radicle) also emerge from the grain.

Shortly after the radicle has emerged, the coleoptile—a sheath that protects the embryonic leaf—grows upward. Is is pushed through the soil by elongation of the mesocotyl. The coleoptile eventually emerges from the soil, after which the first leaf splits the coleoptile and expands. Adventitious roots (roots that develop on the nodes of the sorghum stalk) begin to grow soon after.

Grains of white sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Photo by Thamizhpparithi Maari (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

Germinated sorghum seeds. Photo by Sharon Dowdy (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

Post-germination vegetative growth

Sorghum seedlings emerge about three to ten days after the sorghum grains are planted. Emergence begins the vegetative growth phase, which includes all of the plant’s growth between germination and flowering.

As in other plants, sorghum growth occurs through cell divisions that occur in regions called meristems. Meristems that add length to the plant body—called apical meristems—can found at the tips of shoots and roots. The meristem at the tip of a shoot adds new cells to the stem and is also the region where new leaves begin to form, thus establishing the pattern of leaves on the stem.

The sorghum plant produces a total of about 15 to 18 leaves, although some may wither before the plant is mature. The final leaf to form, called a flag leaf, is the highest leaf on the stem and occurs just below the inflorescence, which is also called a panicle or head.

After all the leaves are initiated (have begun to develop), the shoot apical meristem switches from making new leaves to forming the reproductive structures. This stage, called panicle initiation or growing point differentiation, occurs about a month or more after emergence. During this stage, the stem internodes and the leaves elongate quickly.

In some circumstances, sorghum plants may form tillers. Tillers are shoots that sprout from near the base of a grass plant. If growing conditions are right, sorghum tillers may become large, develop their own inflorescences, and produce additional heads of grain.

Seedlings of sorghum cultivated for biofuel. Photo by PETROSS-TERRA-MEPP & WEST on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Young sorghum plants in a field. Photo by PETROSS-TERRA-MEPP & WEST on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

A field of sorghum plants on which the inflorescences have not yet developed. The plants is this image are from a relatively tall variety of sorghum developed for biofuel. Photo by PETROSS-TERRA-MEPP & WEST on flickr (Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Reproductive growth

Reproductive development is the process of flower growth and development, and, following pollination and fertilization, fruit and seed development. In sorghum, one panicle (a type of branched inflorescence) will develop at the end of the stem. When the panicle begins development, it is not visible on the outside of the plant. During the boot stage, when the plant is about seven to nine weeks old, the panicle is wrapped within the flag leaf, but it is large enough that it is visible as a swollen area in the leaf sheath.

After the panicle emerges from the flag leaf, sorghum diverts its energy to reproduction, and the plant’s vegetative growth rate slows. The plant begins to flower. Flowering takes about four to ten days.

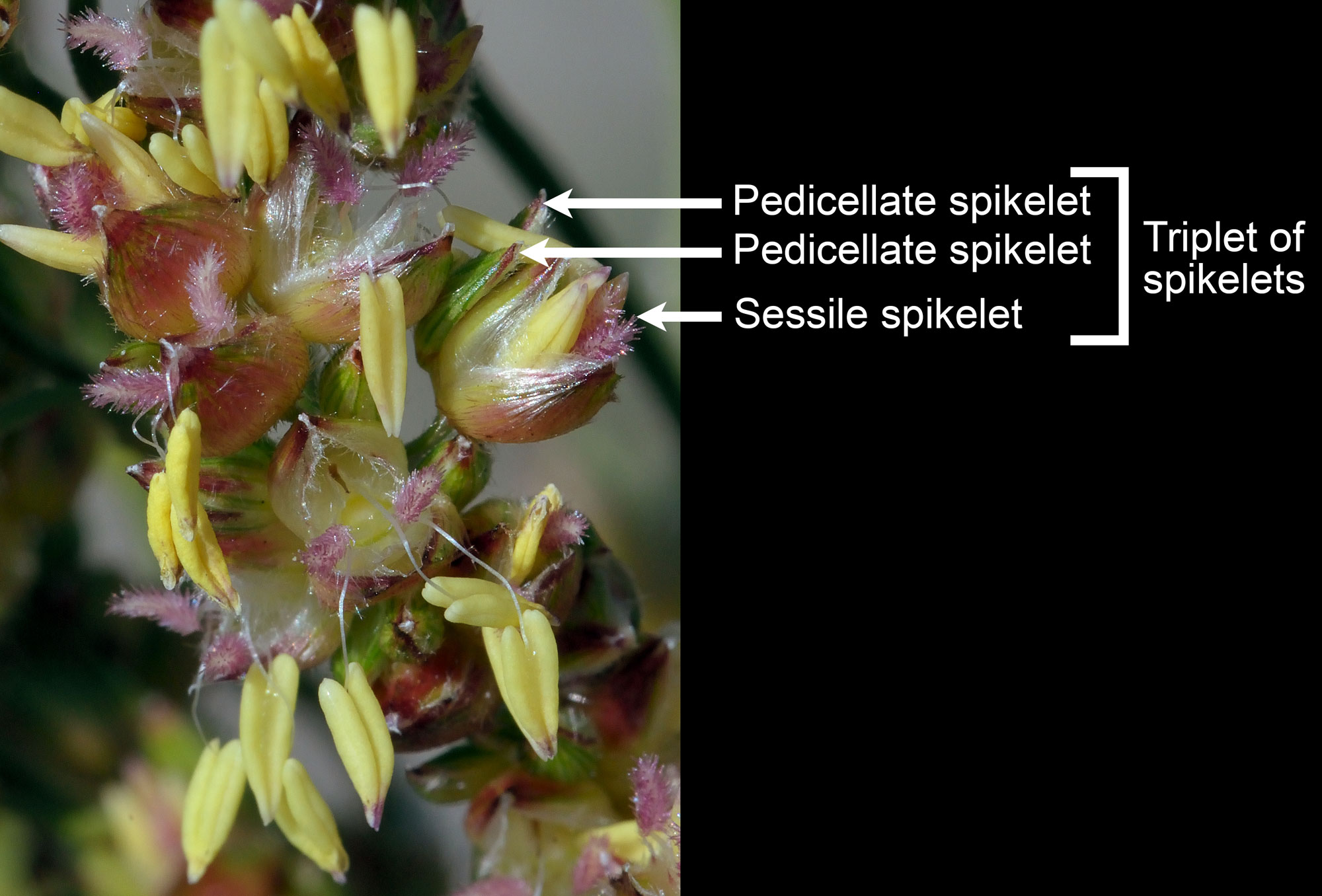

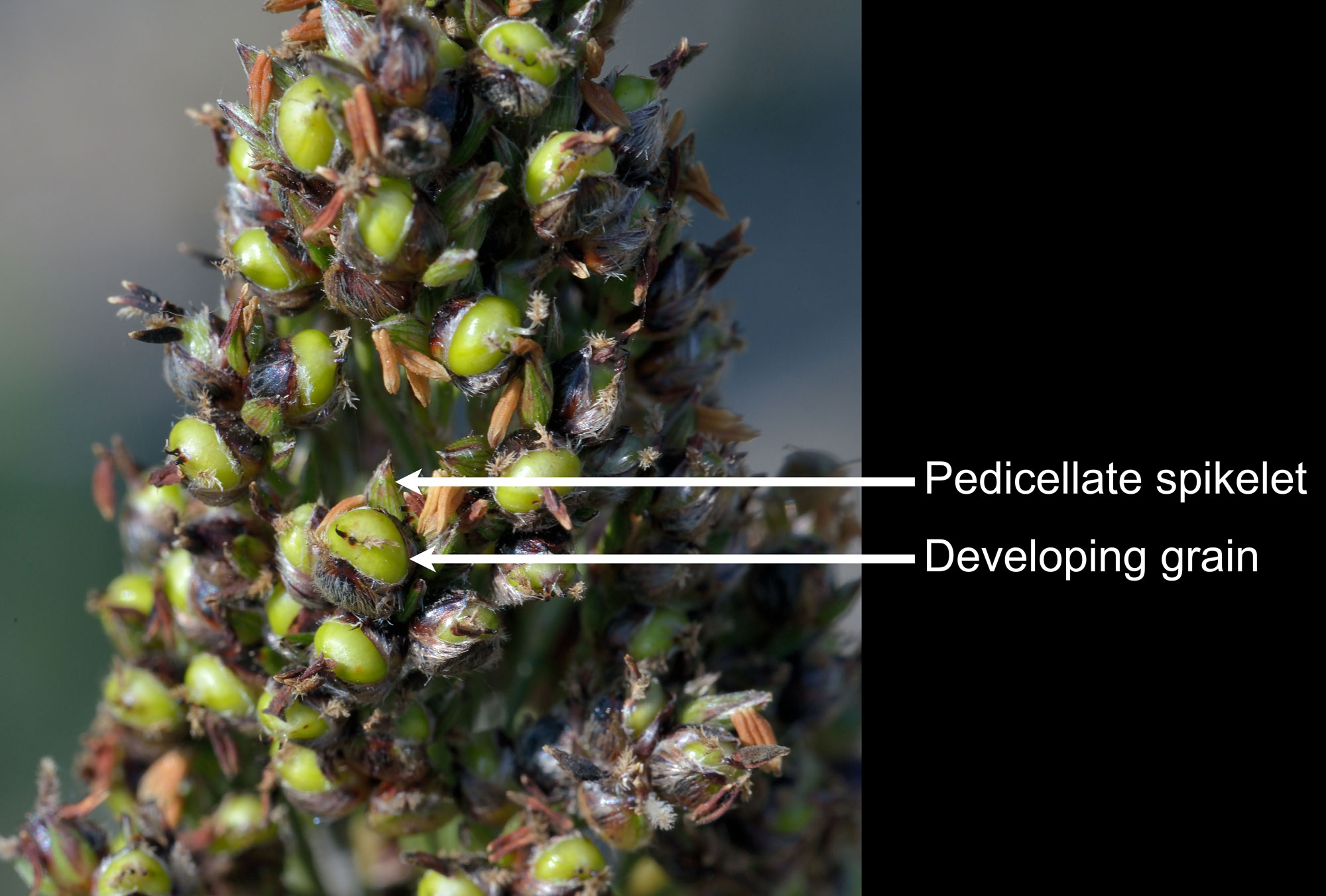

Each sorghum panicle has many spikelets, some without stalks (sessile spikelets) and some with stalks (pedicellate spikelets). Each stalkless spikelet has one bisexual floret; in other words, each stalkless spikelet has one small flower with both stamens and a pistil. Stalked spikelets have male florets (pollen-producing florets) or are sterile (have no functional reproductive organs).

Cultivated sorghum is a mostly self-pollinated crop, meaning pollen released by one plant tends to fertilize the ovules of the same plant. Once the bisexual florets are pollinated and fertilization takes place, they will develop into grain. The male florets and sterile spikelets will not develop into grain.

A field of sorghum in flower. Photo by F. Delventhal (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Spikelets of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). Sorghum has sessile and pedicellate spikelets. The sessile spikelets are bisexual (male and female), whereas the pedicellate spikelets may be male or sterile. Notice the feathery purple stigmas and the yellow anthers on the bisexual florets. Photo by Rasbak (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized and labeled).

Spikelets of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), following pollination and fertilization. Sorghum has sessile and pedicellate spikelets. The sessile spikelets develop into grain after pollination and fertilization, whereas the pedicellate spikelets do not. Notice the brownish anthers that have already released their pollen. Photo by Rasbak (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized and labeled).

Fruit maturation (grain filling)

After fertilization, sorghum grains go through a series of developmental changes in which they accumulate starch and lose moisture. At maturity, each grain contains an embryo, food for the embryo (endosperm), one embryonic leaf (a cotyledon called the scutellum), and an outer protective layer called the pericarp or fruit wall.

Diagram of a caryopsis (grain) of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) in longitudinal section, 20 days after flowering. Source: Modified from figure 3 in Shankar and Dayanandan (2020) Notulae Scientia Biologicae 12: 852-868 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license).

The developmental stages that sorghum grains pass through are as follows:

Soft-dough stage: Shortly following pollination and fertilization, the bisexual florets in the sorghum head begin to develop into grains. At this stage, the plant shuttles resources from the stem to the developing grains. The grains reach about 50% of their eventual total dry weight during this stage, but they are still high in moisture.

Hard-dough stage: During the hard dough stage, resources from the vegetative parts of the plant continue to be shuttled to the developing grains. The grains continue to accumulate mass up to about 75% of their eventual total dry weight, and the amount of moisture in the grains drops.

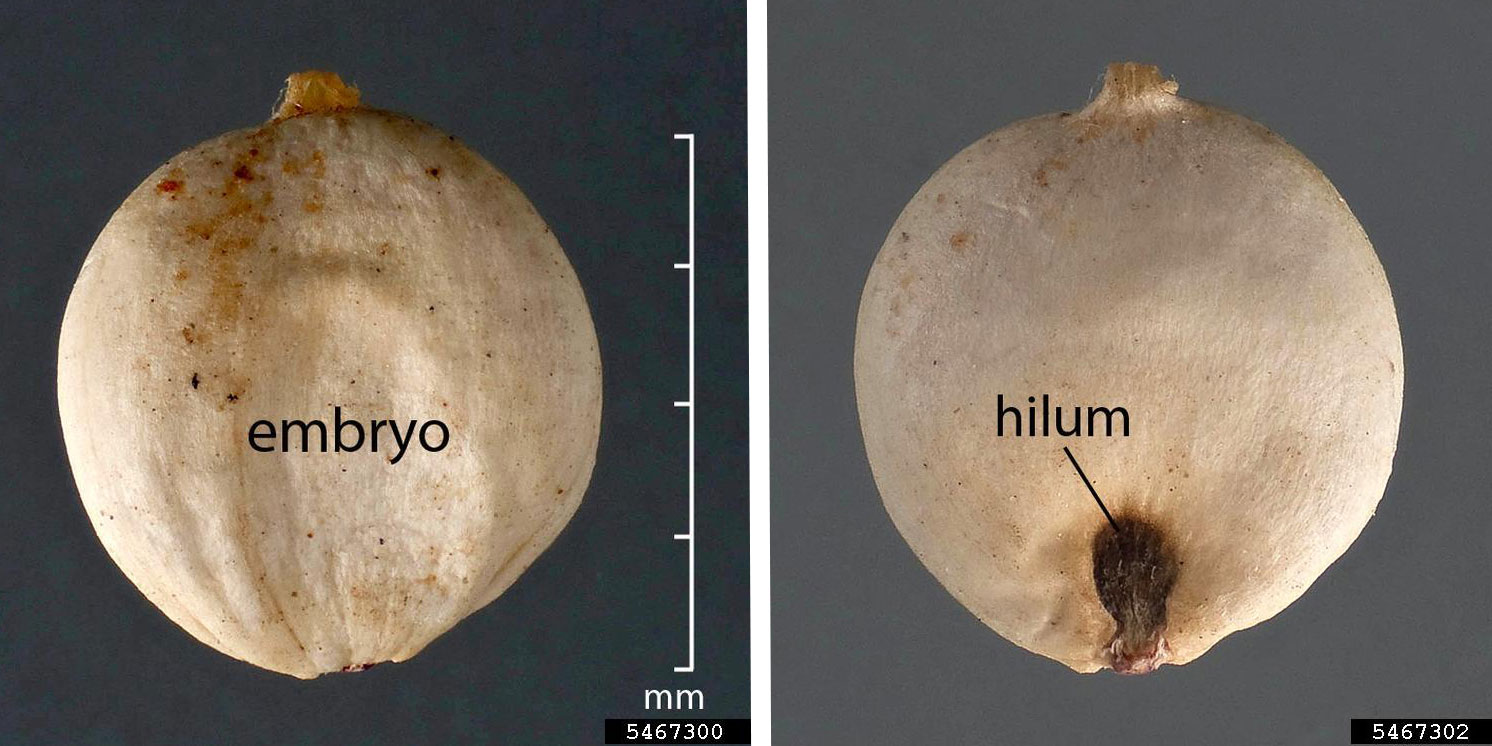

Physiological maturity: A grain reaches physiological maturity when a dark layer of tissue forms at its base, blocking further growth. This layer (the hilum) can be observed on the outside of the grain when it is mature. At this stage, the embryo is fully developed and starch storage is complete. Mature grains usually have 25% to 35% moisture content. Physiological maturity may be reached a month or more after pollination.

After sorghum panicles reach physiological maturity, they are ready to be harvested.

Inflorescence of sorghum or jowar (Sorghum bicolor) with developing grain. Photo by MGB CEE (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Two sides of a grain of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). The depression on one side shows where the embryo is. The hilum on the other surface is the attachment point of the grain. Note that the hilum is dark in color, indicating that the grain is mature. Left photo and right photo by D. Walters and C. Southwick, Table Grape Weed Disseminule ID, USDA APHIS PPQ (Invasive.org, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States license, images cropped).

Hand harvesting sorghum, Burkina Faso. The man appears to be holding a sickle, or a tool with a short, curved blade. Photo by Rik Schuiling/TropCrop-TCS (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Mechanized sorghum grain harvesting, Navasota, Texas, U.S.A., 2013. Photo by Bob Nichols/USDA (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

Resources

Websites

How a sorghum plant develops (Billy E. Warrick, Professor and Extension Agronomist): http://www.soilcropandmore.info/crops/sorghum/sorghum.htm

Growth and development [of sorghum] (Sorghum Checkoff): https://www.sorghumcheckoff.com/our-farmers/grain-production/growth-and-development/

Videos

Growth and development of Sorghum, part 1 (Pioneer Seeds United States, via YouTube): https://youtu.be/EP48t5h1HqM

Sorghum Part IV Reproduction and grain fill (Pioneer Seeds United States, via YouTube): https://youtu.be/AVIXXm4DJNA

Books, articles & reports

Espinoza, L., and J. Kelley (eds.). Grain sorghum production handbook. University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture Cooperative Extension Service. Publication MP 297. https://www.uaex.uada.edu/publications/pdf/mp297/MP297.pdf

Rao, S. S., M. Elangovan, A. V. Umakanth, and N. Seetharama. 2007. Charaterizing phenology of sorghum hybrids in relation to production management for high yields. NRCS-ICRISAT Learning Program on Sorghum Hybrids Parents and Hybrids Research and Development, 6-17 February 2077, NRCS and ICRISAT, Hyderabad.

Sorghum growth and development. K-State Research and Extension, document MF3234. https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3234.pdf

Vanderlip, R. L., and H. E. Reeves. 1972 Growth stages of sorghum [Sorghum bicolor, (L.) Moench]. Agronomy Journal 64: 13-16. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1972.00021962006400010005x