Credits: This page is modified from Chapter 4 in Evolution & Creationism: A Very Short Guide, Second Edition by Warren D. Allmon, published in 2009 by the Paleontological Research Institution (Special Publication 35). Edits and additions for this version by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

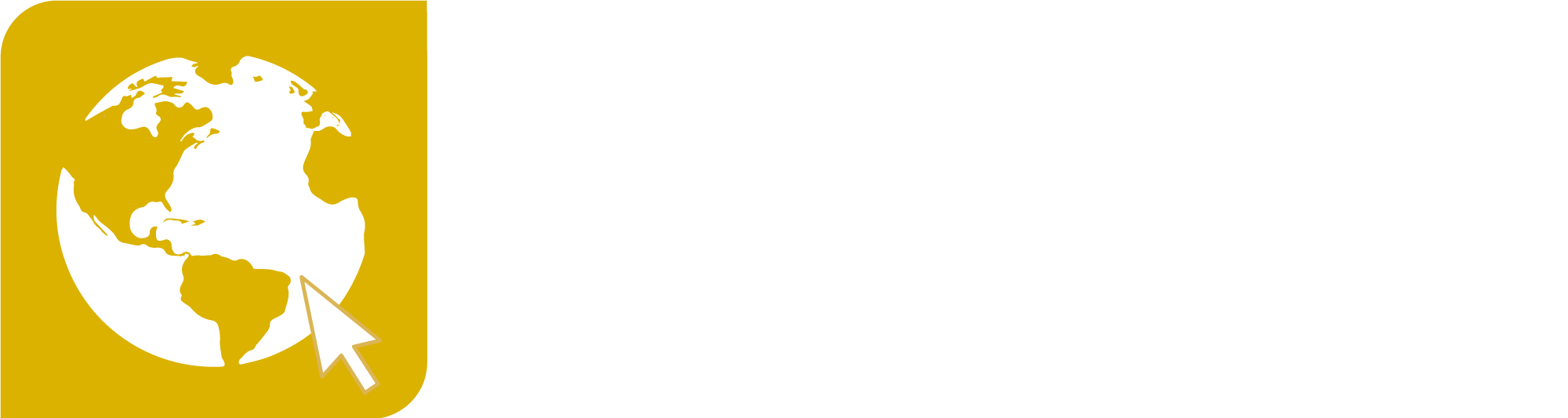

Image above: Cast of the whale ancestor Pakicetus, which lived 50 million years ago. Specimen on display at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Last updated: January 10, 2024.

Introduction

Before Darwin there was no credible explanation for observations about living things, other than to say “God made them that way” or simply “they just are that way.” Such explanations, however, are unsatisfying as science because they are not testable or falsifiable, and they do not lead to any greater understanding. Darwin was not the first to propose a scientific theory to explain the features, history, and distribution of living things. He was, however, the first to offer a purely materialistic, physical hypothesis that was closely argued, supported by abundant evidence, and appeared to explain a wide array of observations about organisms. Such a successful explanation provides powerful evidence that a theory is correct. There are three major “observations about organisms” that the theory of evolution seeks to explain:

Life's order

Why do organisms have the arrangements, relationships, forms, geographic distributions, and patterns of similarity and difference that they do? Any acceptable scientific answer to such questions must explain one of the most obvious characteristics of living things: their frequently close “fit” or “suitability” to do what they do, the phenomenon usually called adaptation. However, a successful theory must also explain features that are not especially suitable for the life of the organism that displays them. Evolution by natural selection (Darwinism) explains all of these observations by suggesting that organisms are related to each other in genealogical patterns (“family trees”) and have evolved, mostly but not exclusively as a result of natural selection, to fit as well as possible – given the limitations of the genetic and anatomical structures they inherit – into their places in nature.

The goodness of fit of organisms to the environments in which they live is a ubiquitous feature of life's history. Consider, for example, the teeth of a squirrel, which are well adapted for opening the seeds that it eats. Photograph by Michael Sauers (Flickr; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license).

Life's history

The fossil record offers unavoidable evidence that life has had a long history of dramatic change. An important aspect of this history is an explanation for not just the success but also the frequent failure of organisms, because the vast majority of species that have ever lived on Earth are extinct. Evolution by natural selection explains life’s history by suggesting that all life shares a distant common ancestor, which gave rise to all of the organisms that followed, and that the changes of life over the past 3.5 billion years are a result of the struggles of individual organisms to survive and reproduce in a spectrum of changing environments.

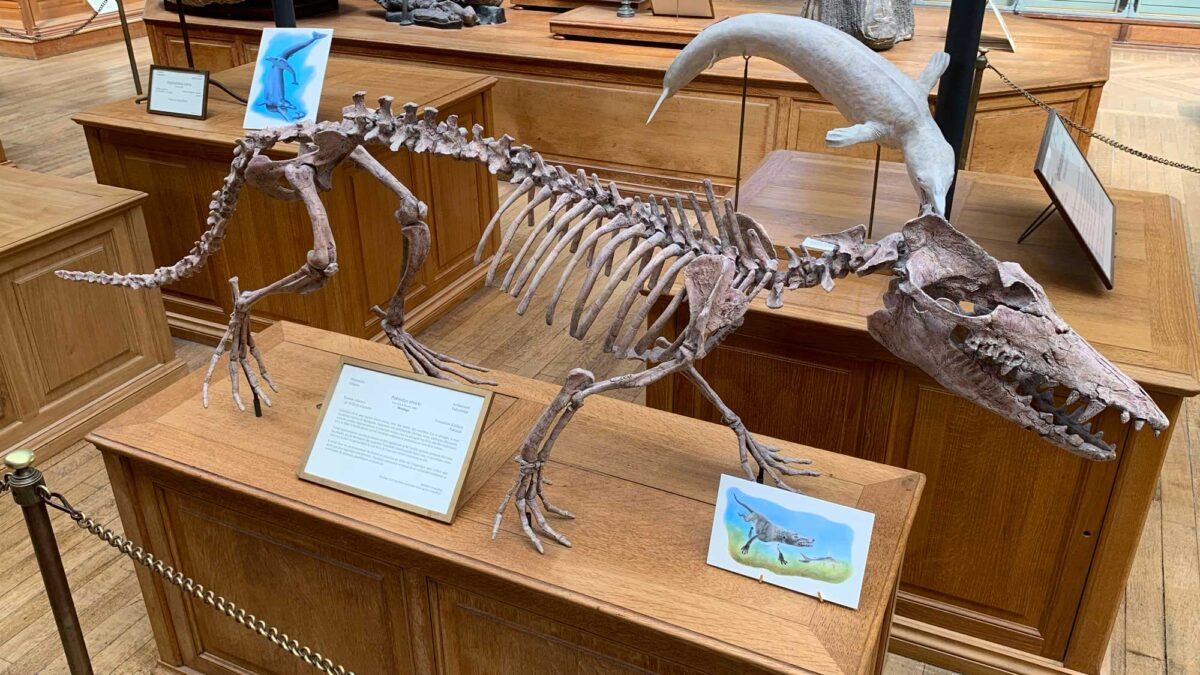

The trilobite Eldredgeops rana from the Middle Devonian Ludlowville Formation of Genesee County, New York (PRI 70712). Trilobites are extinct arthropods that lived in marine habitats during the Paleozoic Era.

Life's diversity

The history of life is not just the history of change in form. Life on Earth – now and in the past – also shows astonishing variety. Evolution by natural selection argues that the history of this incredible diversity of life – like the comings and goings of characters in an enormously long play – are the result of the struggles of individual organisms to survive and reproduce in a spectrum of changing environments.

A small sampling of the diversity of ancient and modern plant and animal life on Earth. Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks for the Digital Encyclopedia of Ancient Life.

Why are modern scientists so convinced that the explanations of life’s order, history, and diversity offered by evolution by natural selection are so compelling? It is important to note that some observations about life are explained by (and therefore provide evidence for) Darwin’s first argument – descent with modification – and others are explained by (and offer evidence for) his second argument – the mechanism of natural selection. We will divide our discussion into Darwin’s two arguments, starting with descent with modification, and then (here) consider its causes.

The evidence for descent with modification can usefully be grouped into six categories: 1) observed small changes; 2) biogeography; 3) comparative anatomy and evolutionary "vestiges"; 4) fossils; 5) classification; and 6) genetics.

1) Observed small changes

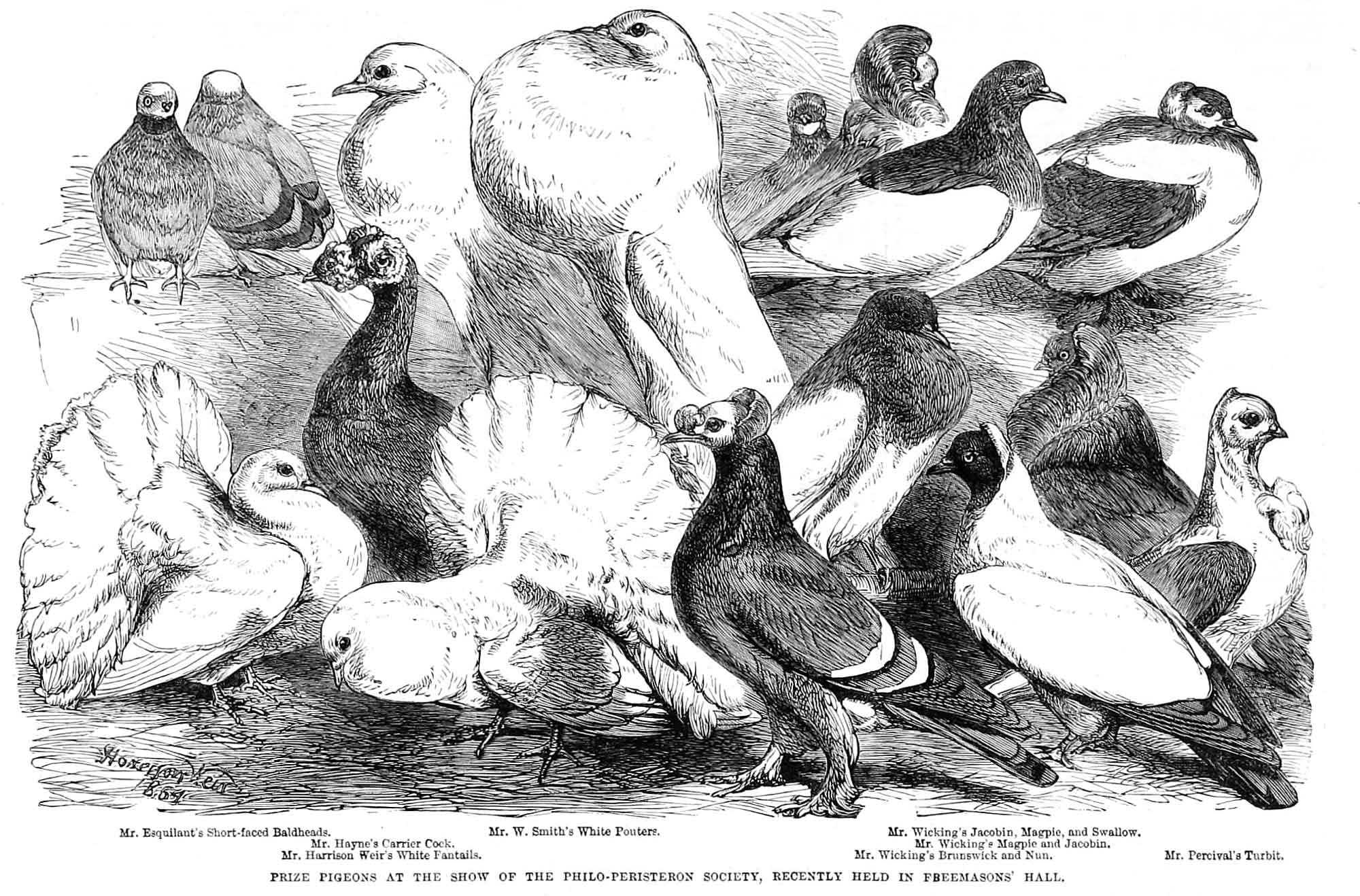

The first chapter of the Origin of Species is about pigeons. Darwin wanted to draw his readers’ attention to an analogy between change under domestication and change in nature.

1864 illustration from the Illustrated London News showing different varieties of pigeons formed through artificial selection (Wikimedia Commons; public domain).

For example, humans can see, or have seen in historic or recent prehistoric times, the change of wolves into Pekinese, grass into corn, wild cows into Herefords, wild ponies into quarter horses, jungle fowl into oven roasters, and many more. Since Darwin’s time, we have watched fruit fly populations change in the laboratory from forms with wings into ones without, among many other changes. We can even create what would be called new species if they were found in nature. In domesticated plants and animals, we can actually watch changes occur generation to generation. We can also watch accidental human-induced changes, such as the spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria, pesticide resistance in insect pests, or changes in the HIV virus that causes AIDS. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we experienced different waves of infection as new varieties of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus evolved (e.g., Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants).

In nature we can also see small-scale changes on short time scales. This kind of small-scale evolutionary change is often called “microevolution.” Darwin’s comparison with domesticated plants and animals was more than an analogy. Agriculture and other selective breeding activities are not like evolution – they are evolution, albeit evolution mediated by humans. Darwin argued that such observations on the short time scales available to us can be reasonably extended into much longer time scales to explain the history of all life. That is, he argued for applying extrapolation to questions about the history of life. Scientists use extrapolation all the time: they observe or experiment on what they have access to and then infer that the results are applicable to what they cannot directly observe or manipulate. If we reject this method for evolution, we must seriously question it in all other areas of science, including those that make possible all of the technology and medicine that make modern life possible. Critics of evolution often argue that, although they accept microevolution (because they can’t deny it since it happens almost before their eyes), they do not accept so-called “macroevolution,” which scientists believe occurs over thousands to millions of years, because such change cannot be witnessed within a human lifetime. In other words, such critics reject extrapolation as a valid scientific method as applied to living things. They do not understand (or do not admit) that they are rejecting the use of extrapolation in one field of science (in which they don’t like the conclusions) but accepting it in others.

2) Biogeography

Why are different kinds of organisms located where they are on Earth? Darwin wondered about why organisms should be distributed so particularly over the Earth’s surface; what logical process could create such a distribution? There are two principal types of biogeographic distributions that provide compelling evidence for evolution:

Similar habitats have different species

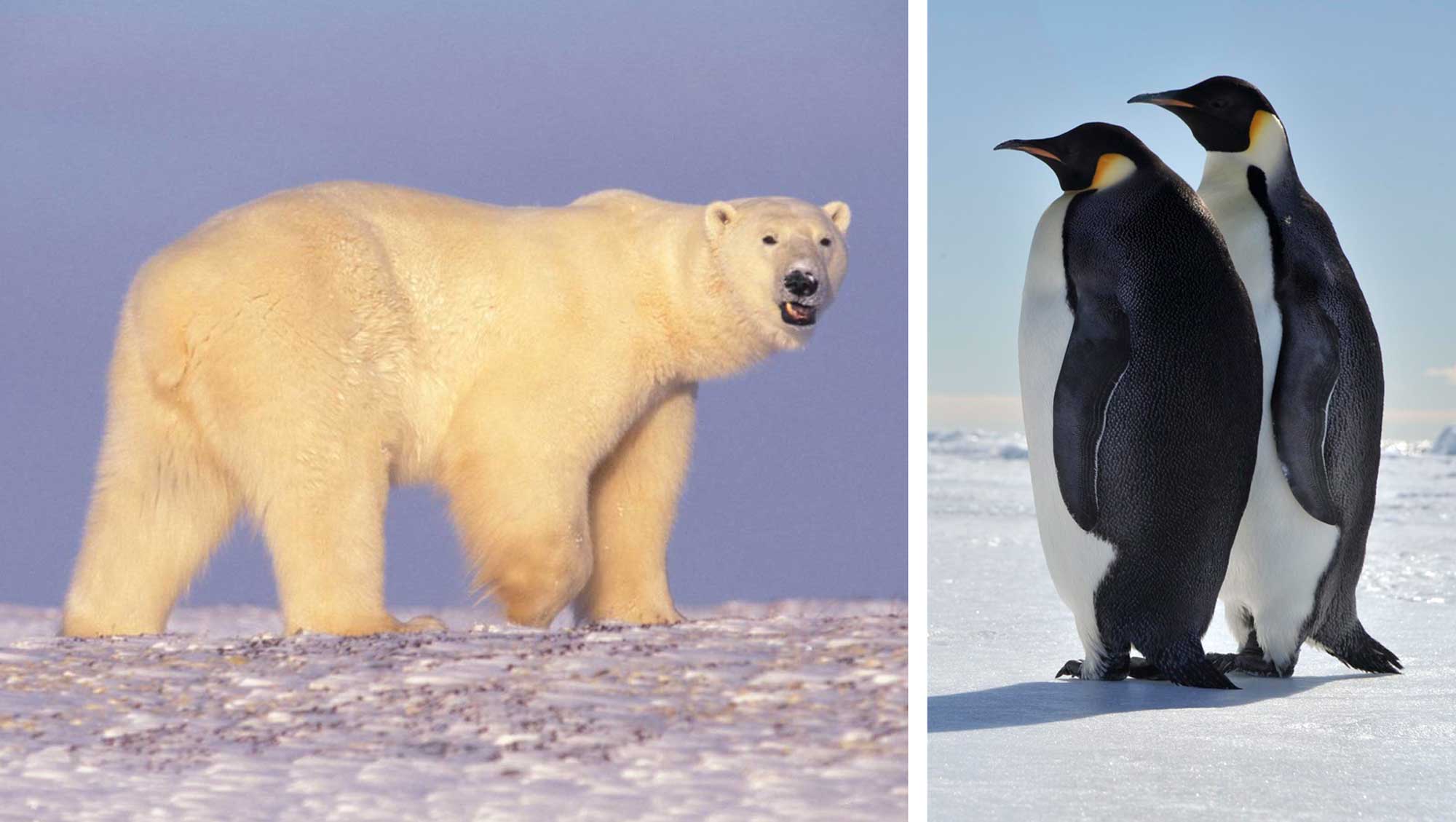

Coral reefs in the Red Sea and in Jamaica are both built largely of coral and algae. They both inhabit essentially similar conditions of temperature, depth, sunlight, and nutrient abundance. Yet of their thousands of species, almost none are in common. Why? The corals of Jamaica could probably survive in the physical conditions of the Red Sea, yet they are not there. Why not? Similarly, the North and South Poles are similar in climate and physical condition, yet penguins do not live at the North Pole and polar bears do not live at the South Pole. They could, but they don’t. Why? Nearly all organisms are limited in their geographic range, so these are just a few of millions of examples.

Polar bears and penguins live in similar habitats, but on opposite poles of the Earth. Polar bear image from Terry Debruyne/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Flickr; public domain; image cropped and resized); Penguin image from the U.S. Embassy in New Zealand (Flickr; public domain; image cropped and resized).

Why don’t the same organisms live everywhere that they can possibly live? Evolution explains these patterns as the result of history. These organisms have evolved from ancestors that lived in different places. The corals of the Red Sea were changing over time independently of the corals in Jamaica, so that the species in these two places differ slightly in biological detail. Penguins evolved from ancestors that never made it to the northern hemisphere, and polar bears evolved from ancestors that never made it to the southern hemisphere.

Nearby locations have similar species

Darwin was particularly impressed that the animals of the Galapagos Islands, located more than 600 miles off the west coast of South America, are most similar to those of the South American mainland. Why should this be so? Why are the organisms of the Caribbean islands most similar to those of the surrounding American mainland? Why aren’t they more similar to, say, those of Africa, or Asia? This is a pattern typical of all organisms. Evolution explains such patterns as results of history – organisms evolving from an ancestor and moving to a nearby habitat.

3) Comparative anatomy and evolutionary “vestiges”

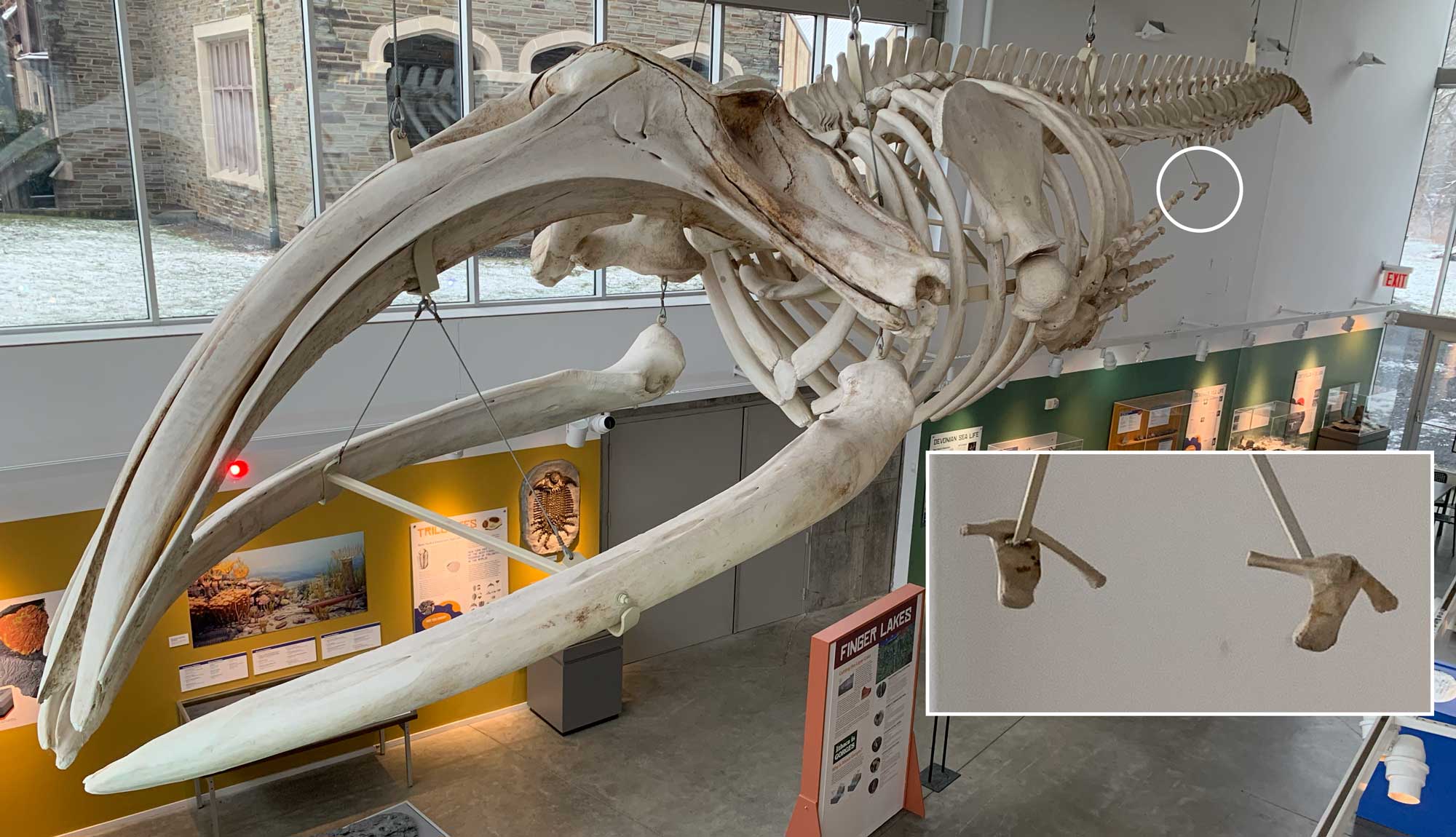

As mentioned above, when we look at living things – from bacteria to plants to animals – we cannot help but be impressed by how well “fit,” “suited,” or “adapted” they frequently are to their environments and ways of life. For example, an insect has color patterns that enhance its ability it to blend in with its background and thus escape predators, or a predatory mammal has teeth that allow it to quickly kill and consume its prey. These kinds of observations are the standard stuff of descriptive natural history, and (as discussed below) natural selection explains them very adequately. Yet organisms also show features that seem to be the reverse – to have no apparent function or adaptive value, or to have functions very different from those they were apparently originally built to perform. For example, ostriches and many other birds are flightless but nevertheless have wings; many vertebrates that normally lack hind limbs, such as snakes and whales, nevertheless frequently have small bones inside their flesh under their tail; most humans can’t wiggle their ears but all of us have ear muscles.

The skeleton of Right whale #2030, on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, NY. Note the pairs of small bones suspended below the tail. These bones appear to have no function today. Evolution explains them as vestiges of the hind limbs of whale ancestors that lived on land 50 million years ago (see image of Pakicetus at top of page). Image by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Such features, often referred to as vestigial organs or simply vestiges, are difficult to explain by means of theories like the “argument from design.” Yet they are easily explained by (and are powerful evidence for) descent with modification. This explanation is not, however, for the reasons that are sometimes given. Some evolutionists have pointed to supposedly vestigial structures as evidence of evolution by arguing that an “intelligent” creator would not have designed living things with parts that seem fashioned for other purposes or that have little or no function at all. Although provocative, this is not an adequate explanation, because science has no way to test what would or would not be sensible from a supernatural creator’s point of view. Furthermore, features that might at first seem to have no function could later be shown to have functional importance.

Vestiges are evidence for evolution because they often show a pattern across different species similar to what would be predicted if they were inherited from a common ancestor, rather than designed from scratch to meet the needs of just that one species. It isn’t just that organisms have features that look like ad hoc or jury-rigged solutions. It is that they have features that look like they were jury-rigged in a particular sequence – through time as represented by fossils or in the classification of modern species. Organisms bearing such vestiges (and all do), therefore, do not appear to have been designed and built independently to meet the challenges of life with optimal engineering solutions, rather they appear to have been built to respond as well as they can to changing environmental demands by altering whatever was present at the moment. The process of comparing species to document these patterns of similarity is called comparative anatomy.

This question of the origin of vestigial structures is particularly interesting when we look at the earliest stages in the lives of organisms – the form of their embryos. Why do embryos look as they do? Why do they pass through the stages that they do? Why do human embryos have tails and gills? Why do bird embryos have teeth? Why do snails start out untwisted and then twist (and then sometimes untwist)? There are innumerable other examples. Evolution explains such features – in embryos and adults – as the traces of history. According to evolution, organisms have many features that do not make sense in terms of their current function, but were inherited from an ancestor that used them in a different way. We all have ear muscles, for example, because a distant ancestor used them to move its ears.

4) Fossils

The fossil record provides perhaps the clearest evidence for evolution, for it offers clear indications that organisms have changed through time and that there were different assemblages of species living at different times in the Earth’s history. Critics of evolution frequently say that the fossil record contains no “transitional forms,” presumably implying that the different fossils not linked by such forms were separately created. But this is simply incorrect. Literally thousands of fossils are known that are intermediate in their body form between other younger and older fossils.

The Devonian "fishapod" Tiktaalik, which had transitional features of both lobe-finned fishes and four-legged vertebrates (tetrapods). Specimen (cast) on display at the Museum of the Earth, Ithaca, New York. Photograph by Jonathan R. Hendricks.

Fossil evidence for evolution can be divided somewhat arbitrarily into “large scale” and “small scale” patterns. In both cases the interpretation is the same: sequences of fossils appear in the rocks that are most easily interpreted (by reasonable extrapolation) as ancestor-descendant series, undergoing change in appearance. Recognizing that stacked layers of sedimentary rocks represent a span of time for deposition, it is difficult to understand the patterns in any other way. The fossils in these sequences are similar to frames in a cartoon or motion picture. The images in these frames do not actually move; we infer motion when we look at them in a series. More frames per second makes the motion look smoother, and fewer frames per second makes the motion look less smooth and more discontinuous or “jerky.”

“Large scale” patterns are those that span tens or even hundreds of millions of years. Although there can be gaps of millions of years between rock layers that contain somewhat different-looking fossils, the fossils in successive layers look undeniably more similar than do fossils in more widely separated layers. It is possible that the organism in each layer was created separately and destroyed, to be succeeded by a newly created form that was just a little different. Evolution explains these patterns, however, as results of changes occurring during ancestor-descendant transitions.

“Small scale” patterns are sequences of fossils very closely spaced in layers of rocks, showing small but consistent patterns of difference among one another. These patterns would be even more difficult to explain in any way other than evolution, such as with a series of separate creations. They are similar to a cartoon with many frames per second – the inferred motion is highly believable because the changes between each one are so small. This is not something occasionally seen in just a few cases. They have been documented thousands of times by millions of fossils, collected over more than 200 years for scientific study and commercial applications such as petroleum geology. The consistency of these patterns is what gives them great value and provides us with confidence in our interpretation.

5) Classification

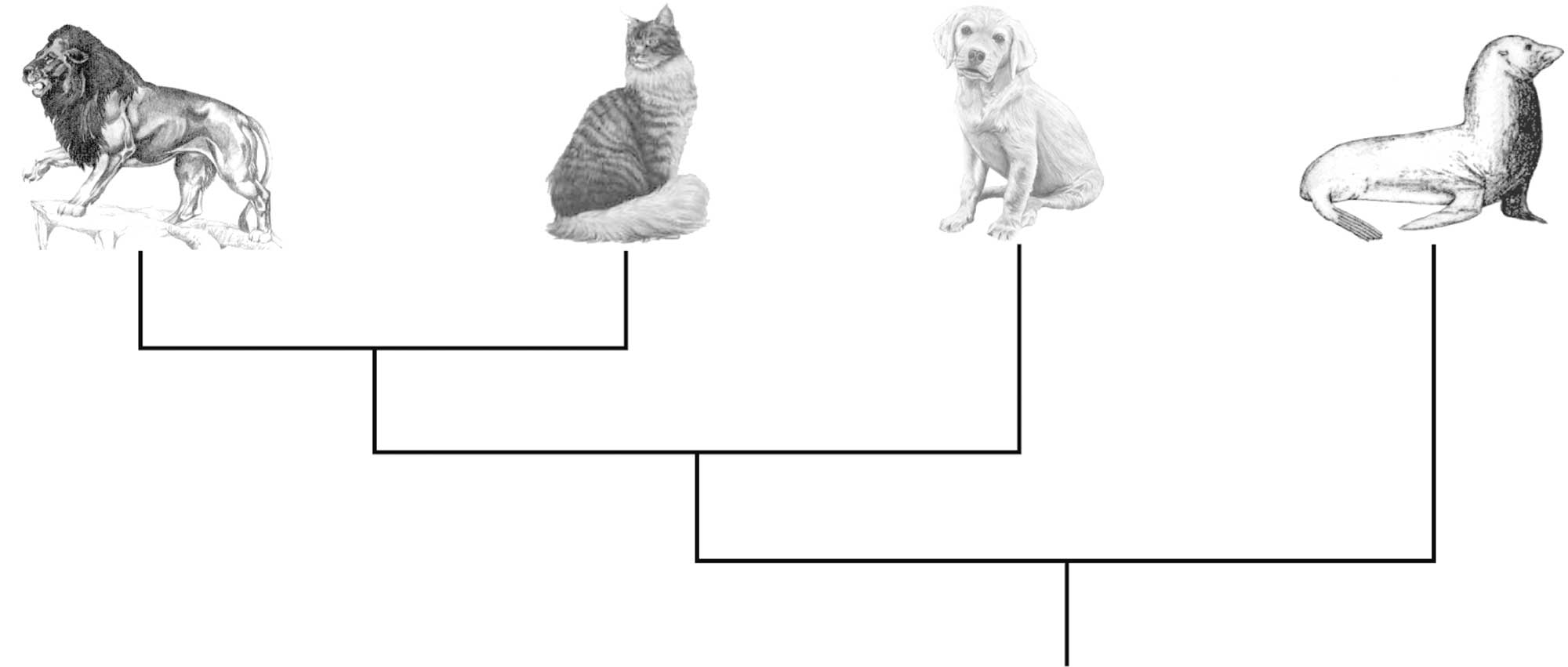

Life is not arranged randomly and living things do not form a “smear” of variation. Organisms show patterns of similarities and differences that allow us to arrange them into groups, and to arrange these groups into groups, and so on. This hierarchical pattern is easily explicable by postulating that groups of organisms are connected by genealogy.

Classification as evidence of evolution. When we try to classify modern carnivorous mammals (and all other living things) into groups, we end up with a group- within-group, or hierarchical, pattern. Evolution explains this as a result of a branching family tree, in which groups that shared a more recent common ancestor share more similarities with each other than with groups with which they have a more ancient com- mon ancestor.

For example, all cats (lions, leopards, domestic cats, etc.) can be grouped together on the basis of their many shared features (such as retractable claws). Dogs and their kin (wolves, etc.) can be similarly grouped together on the basis of shared features (such as aspects of their teeth). However, cats and dogs can also be grouped together with other groups such as bears, seals, and weasels, because these groups share many features (for example, they are all carnivores and have numerous characters in common related to this, such as sharp claws and teeth). Carnivores are mammals, that is, can be grouped with other mammals, such as elephants and rodents, and so on. This “group-within-group” arrangement is explained by evolution, suggesting that the different kinds of cats share a more recent common ancestor with each other than any of them do with dogs, but dogs and cats share a more recent common ancestor than either group does with mice, etc.

6) Genetics

All organisms on Earth contain RNA (ribonucleic acid) and almost all contain DNA. Virtually all organisms use exactly the same coding mechanism to read instructions from their genetic material – the same pattern of chemical subunits of DNA code for the same amino acids in oak trees and whales and people and mushrooms. Furthermore, all of the amino acids in living things on Earth are arranged the same way – all are “left-handed,” even though “right-handed” forms also exist and have essentially identical chemical function. Why is this? Evolution explains this pattern by suggesting that all living things on Earth share a single common ancestor that contained RNA and left-handed amino acids, and this ancestor passed these features on to all of its descendants.

It is notable that Darwin did not know anything about genes or DNA when he wrote the Origin of Species in 1859. The existence of genes was not widely known until the early 20th century and the structure of DNA was not discovered until 1953. Yet the structure and function of genes and DNA are fully consistent with the hypothesis that organisms share a common ancestor and have changed through time – that they have evolved. In this sense, genetics has been an independent test, and confirmation, of the idea of evolution.

Summary

- Any adequate scientific theory of biology must explain at least the observed order (including both adaptation and nonadaptation), history, and the diversity of life.

- Pre-Darwinian explanations for these observations were largely theological, notably including the “argument from design,” with which Darwin was very familiar.

- Evolution (in the sense of descent with modification) is an explanation for many of these observations. Natural selection as a cause for evolution is an explanation for others.

- The evidence for evolution can be grouped into six categories: directly observable small-scale change, biogeographic distribution, comparative anatomy, the fossil record, classification, and genetics. Each of these categories includes countless compelling pieces of evidence that descent with modification is true.