Page snapshot: Summary of the history of sugarcane, including its wild relatives, domestication, spread, and place in history, including the history of slavery.

Topics covered on this page: Introduction; Making sugar from sugarcane; Early technology (through the 1800s); Planting and harvesting; Milling and refining; Newer technology (1800s to present); Origin and early spread of sugarcane; Initial domestication and spread (New Guinea, Asia); Later expansion (Middle East, North Africa, and Europe; Sugarcane in the Americas, 1400s to 1900s; The beginning: Madeira, São Tomé, and Canary Islands; First sugar-producing colonies in the Americas; The Transatlantic Slave Trade; Slavery in the United States; Sugar production under slavery; The sugar industry after slavery; Sugarcane in Indonesia, 1700s to 1900s; Dutch colonization and aftermath; Sugar production on Java, late 1700s to 1900s; Industrialization and plant breeding on Java, 1800s to 1900s; Sugarcane production today; Resources.

Credits: Funded by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Page by Elizabeth J. Hermsen (2023).

Updates: Page last updated July 14, 2023.

Image above: A man loading sugarcane near New Iberia, Louisiana, U.S.A., 1938. Photo by Lee Russell (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number LC-USF33-011843-M3, no known restrictions).

Introduction

Sugarcane is in the genus Saccharum. Saccharum may include as many as 30 to 40 species of plants, although many botanists recognize six or even fewer species of domesticated sugarcanes and their wild relatives. The wild species of sugarcane are robust sugarcane (Saccharum robustum), native only to the island of New Guinea, and wild sugarcane (Saccharum spontaneum), native to subtropical to tropical Africa, Asia, and Australasia. Domesticated sugarcane species cultivated for sugar (sucrose) include the original domesticated sugarcane or noble cane (Saccharum officinarum) and hybrid domesticated sugarcanes (S. barberi in India, S. sinense in China, and modern sugarcane cultivars). Another species (Saccharum edule), also native to New Guinea, is cultivated as an edible green (known as Figi asparagus, duruka, or other names).

From its origins on New Guinea, domesticated sugarcane spread around the world. Today, sugarcane is the world's number one commodity crop. While sugarcane is valued for the sweet juices in its stem, the plant has an ugly history. The story of sugarcane is tightly linked to colonialism, indentured servitude, forced labor, and slavery, and sugarcane and sugar production has, through history, cost countess people, primarily Africans and their descendants, their freedom, and many their lives.

Sugarcane patch, Fujian, China. Photo by Vmenkov (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

A broken sugarcane stalk resting on a bowl of refined sugar. Photo by Carl Davies (CSIRO Science Image, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Making sugar from sugarcane

Before discussing the history of sugarcane, it is helpful to discuss how sugar is made from stalks of the sugarcane plant; this will aid in better understanding the technological innovations involved in processing sugarcane as well as the amount of human labor needed to grow and process sugarcane historically. (Today, much of the labor of growing, harvesting, transporting, and processing sugarcane on an industrial scale has been taken over by machines.)

Early technology (through the 1800s)

Planting and harvesting

Sugarcane is not grown from seeds, but is propagated from whole stems or pieces of stems called billets or setts. These may be planted in rows or shallow pits, covered, and fertilized. New upright stalks grow from buds on the pieces of stem. Sugarcane stalks take at least 12 months to grow and mature before they can be harvested. Sugarcane requires fertilization, weeding, hot weather, and a significant amount of water (provided by rain or by irrigation) to grow.

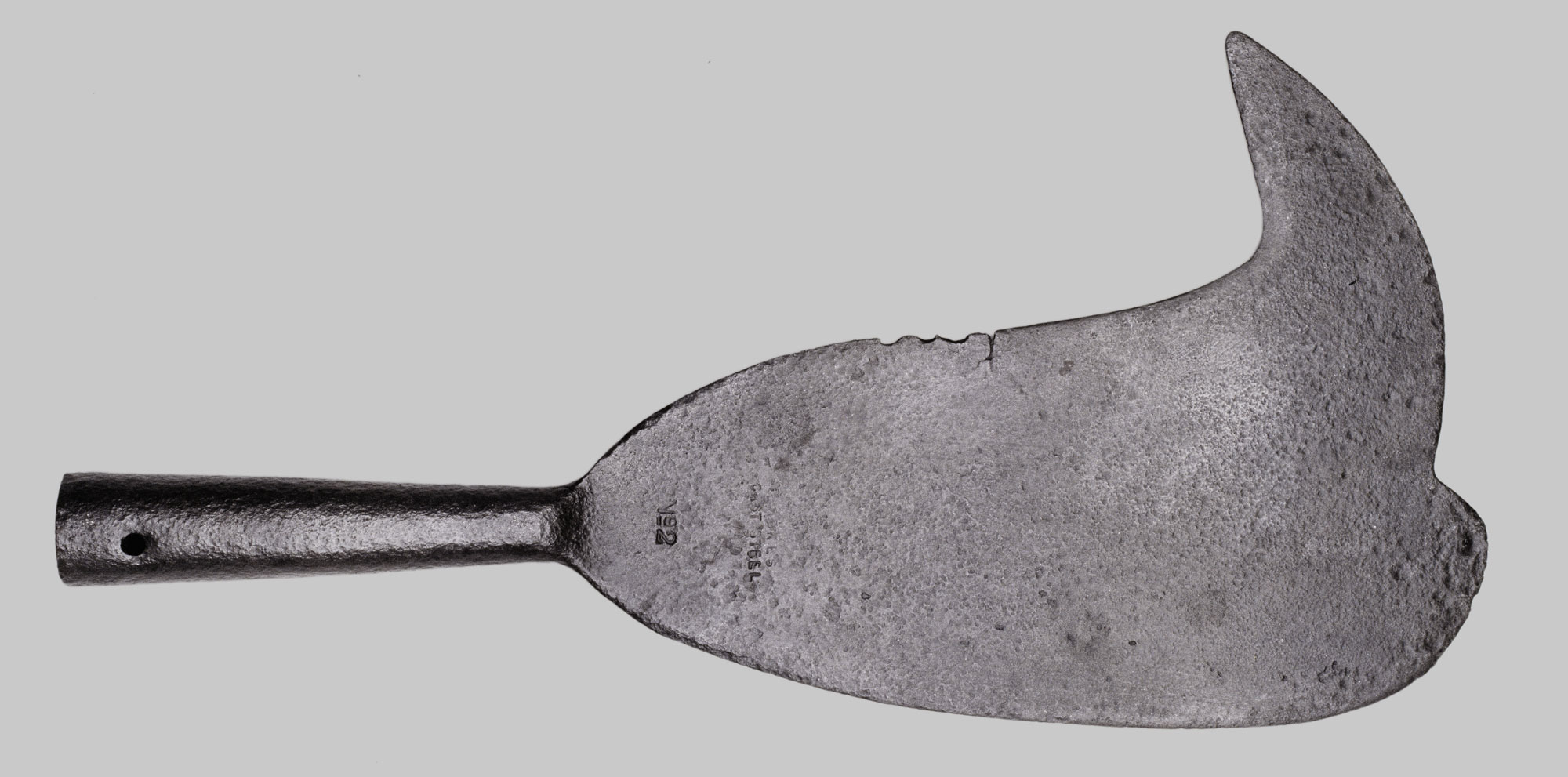

In the past, hand-harvesting was done using a large, curved blade, called a cane knife or a billhook. During harvest, laborers cut the stalks and stripped them of leaves before they were carried to wagons to be taken to a sugar mill, which was located near the sugarcane fields.

People planting billets in furrows, Sevangala, Sri Lanka, 2012. Photo by Ebaran (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized).

A man harvesting sugarcane on Barbados, 1914. Photographer unknown, National Museum of World Cultures (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Milling and refining

Once sugarcane is harvested, it must be quickly processed so the sugary juice in the stalks does not ferment. Sugarcane stalks are crushed to expel the juice, which is captured in a receptacle. In the past (and today in some small, non-industrial operations), crushing was done using edge-runner mills (essentially, a stone that runs over the sugarcane stalks like a wheel), presses, or rollers. These crushing devices may have been operated by human, animal, water, wind, or, later, steam power.

After extraction, the sugarcane juice may be clarified, meaning that substances (in the past, things like lime, egg white, and animal blood) are added to separate out impurities. The juice is then boiled in order to evaporate much of the liquid, which concentrates the sugar. Boiling was originally done in open pans, with people hand-skimming contaminants from the top of the liquid using a skimmer (basically, a tool that looks like a large, shallow spoon or ladle with holes in it) as the sugarcane juice cooked. As the sugarcane juice was concentrated into syrup, it was ladled into smaller and smaller pans, until finally it was ready to be cooled.

After boiling, the concentrated sugar syrup, or massecuite, was transferred to a shallow pan to cool. At this stage, the sugar still contained a relatively large amount of molasses, a dark, viscous liquid that is a byproduct of sugar making. Today, small amounts of solid, unrefined sugar made by cooking sugarcane juice in open pans is still produced in some regions, where it is known by a variety of names, like jaggery.

Engraving depicting sugar-making on Sicily around 1537. In the upper right, men can be seen harvesting sugarcane. In the center foreground, the sugarcane is being cut into pieces. To the left, a man carries cane pieces in a basket toward a hopper; another man can be seen pouring sugarcane pieces into the hopper at the upper left. In the center back, men can be seen operating a press, with the juice being collected in a depression in the floor. To the right, another man pours sugarcane juice into a vat, where it is boiled over a fire. Another man can be seen skimming the boiling juice. In the center right, a man pours the concentrated syrup into molds. Finally, to the right of the men cutting sugarcane, men remove sugarloaves from molds and arrange them on tables. Engraving by Jan Collaert, from New Inventions of Modern Times, ca. 1600 (The Met, public domain).

Vertical rollers used to crush sugarcane to extract the juice, year unspecified ("colonial period"), Mexico. Photo by Thelmadatter (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Large kettles for boiling sugarcane juice in the ruins of a sugar mill at New Smyrna Beach, Florida, U.S.A., 1830 to 1835. Photo by Che-or (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

A man producing jaggery from sugarcane, Karnataka, India. In the photo, a small mechanical sugarcane grinder can be seed in the background, next to a pile of bagasse (crushed sugarcane stalks). In the foreground, a man is stirring a kettle of cane syrup. Photo by Jedesto (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Jaggery cubes. Photo by Mangosapiens (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

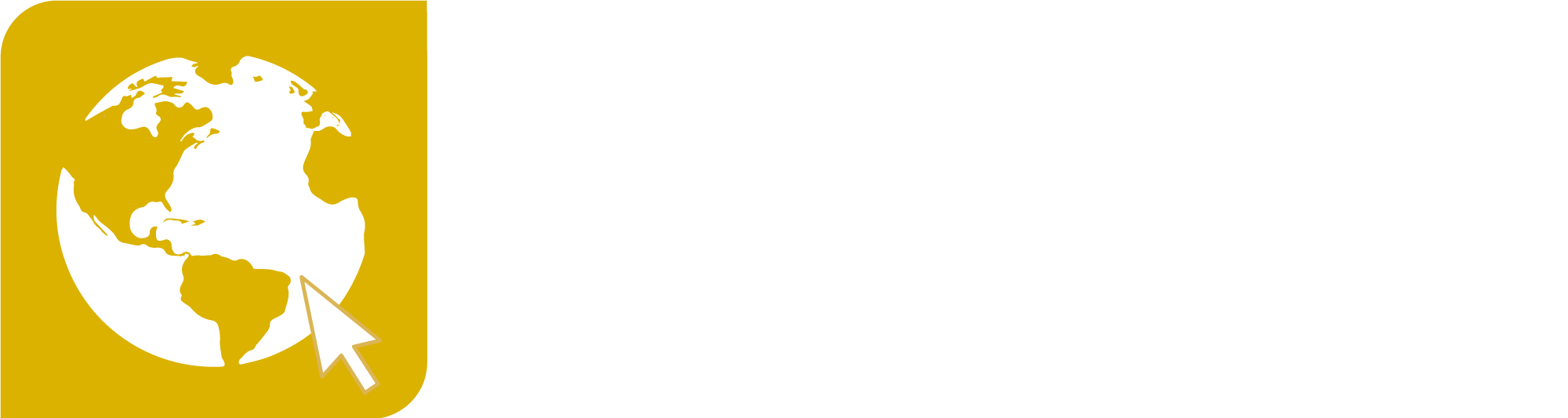

Refining is the process of separating sugar from molasses and other impurities to make purer sugar. In one of the simplest methods of refining, cooled muscovado (unrefined sugar) was transferred into a cone-shaped container that had a small hole in the bottom. Once the sugar had solidified enough, a plug was removed from the hole, and the container was placed with its narrow end down in the mouth of a pot. The molasses would slowly drip through the hole in the base of the cone into the pot below. Water may have been sprinkled over the sugar to aid the draining of molasses, or, alternatively, a wet clay cap may have been placed on the cone, which also provided a small amount of water to help the molasses drain. The solid sugar that remained was eventually removed from the mold and dried.

Sugar from which some of the molasses had been drained was still brownish in color and not fully refined. In order to refine it further, the raw sugar was melted, and the clarifying and boiling process repeated. The reboiled sugar syrup was then poured into a conical mold to allow the molasses to drain off again. The number of times sugar was boiled, solidified, and drained determined the purity of the refined sugar. The finest sugar was triple-refined and white in color.

Once the sugar had been sufficiently refined, it was removed from its mold for the final time as a solid cone called a sugarloaf and dried. Sugar was formed into solid loaves using conical molds through the 1800s. Pieces had to be cut off the sugarloaf and ground so that the sugar could be used. Devices were invented to cut pieces from the loaf, like special sugar nips (scissors) and cutting boxes.

A sugar refinery, image from 1762. In this illustration, molasses is being drained from sugar. The sugar loaves are in the upside-down, cone-shaped pots, which each have a hole in the bottom (see images below). The molasses would drip out of the cone-shaped pots into the round pots beneath them. Image from an encyclopedia by Denis Diderot, 1751 to 1775 (Slavery Images, public domain).

Cone-shaped molds used for making sugar loaves; note that each has a hole in the bottom to allow molasses to drip out into a molasses pot, which would have been placed under the cone. Left: Sugar cone from Castello della Favara Maredolce, Palermo, Sicily, dating before the late 1200s. Right: Sugar cone dating to the 1800s from the Renaud Refinery rue de Richebourg, France. Left image from figure 16 in Mentesana et al. (2022) Minerals 12(4): 423 (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, image cropped and resized); right image by Koreller (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

Sugar nips (left, right, and second from right) and sugar tongs (second from left). Photo by FA2010 (public domain).

A wooden box for cutting sugar loaves, 1833 to 1850. Photo by Wolfgang Sauber (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized).

Newer technology (1800s to present)

Technology transformed sugarcane growing and sugar processing during the 1800s to 1900s, eventually reducing the need for human labor in sugar mills and refineries and also in the fields for planting, weeding, and harvesting.

In industrial operations beginning in the nineteenth century and continuing through today, boiling is done in enclosed containers (called vacuum pans) at low pressure, which lowers the boiling point of the sugar syrup and prevents losses of syrup due to spillage, caramelization, and inversion (inversion is the breaking of the sugar molecule, or sucrose molecule, into simpler sugars). The first vacuum pan was invented in 1813 by Edward Charles Howard.

An important upgrade to the vacuum pan was the multiple-effect evaporator. The multiple-effect evaporator was invented by Norbert Rillieux, who patented it in 1846. Rillieux was a free man of color, the son of a white plantation owner and a free woman of color; he was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, and educated in France. The multiple-effect evaporator was made up of several linked vacuum pans in which sugarcane juice was boiled and concentrated at low pressure using steam heat that was transferred from pan to pan, producing better quality sugar more efficiently than either open pans or single vacuum pans. While Rillieux's invention was prized by sugar millers, he faced severe discrimination in the United States. He eventually moved to France permanently. Multiple-effect evaporators are still used in sugar processing and other industries today.

A continuous vacuum pan, Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company Mill, Maui, Hawai'i. Photo by Fives Fletcher - Fives Cail -Fives Fletcher (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license).

Other important inventions included the filter press and the centrifugal. The filter press removed impurities without the need for hand-skimming the sugarcane syrup. Centrifugals, introduced in the 1850s, spun massecuite to separate sugar from molasses relatively quickly, eventually making the cone-shaped pots previously used for draining molasses obsolete. A more effective type of mill for crushing sugarcane to extract the juice was also invented. In the field, tractors, harvesters, planters, and other farm equipment were progressively introduced, supplanting human laborers in large operations.

Men examining a Wurtele sugarcane harvester, invented by Allen Ramsey Wurtele, 1938, Mix, Louisiana, U.S.A. Photo by Lee Russell (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number LC-USF33-011895-M3, no known restrictions).

A man hauling sugarcane with a tractor and trailer in the region of Clewiston, Florida, 1939. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number LC-USF34-051111-D, no known restrictions).

Origin and early spread of sugarcane

Initial domestication and spread (New Guinea, Asia)

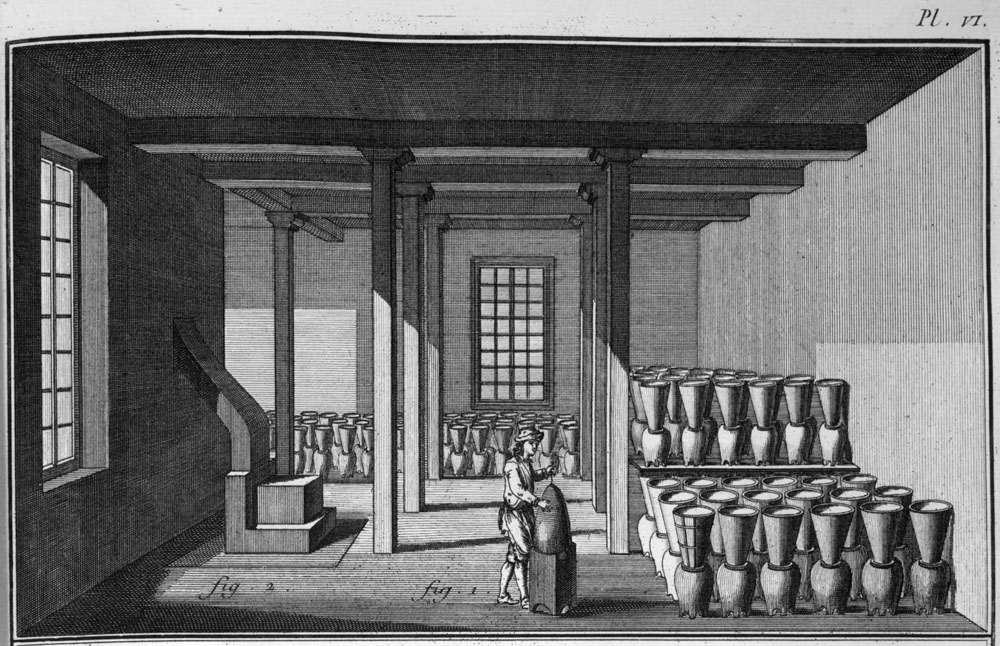

Scientists think that sugarcane (Saccharum officianarum) was first domesticated in New Guinea about 8,000 to 10,000 years ago from robust sugarcane. From there, its cultivation expanded in Oceania (Micronesia and Polynesia) and into Asia, where it reached China and India at least 3000 years ago. The cultivated sugarcanes S. barberi (India) and S. sinense (China) are thought to hybrids of domesticated sugarcane (S. officinarum) and wild sugarcane (S. spontaneum) that originated in those regions; neither is widely cultivated today. The process of producing a type of solid, unrefined sugar from sugarcane was invented in India about 2500 years ago. In China, sugarcane was used as a sweet vegetable, as a medicinal plant, and, perhaps by the East Chin Dynasty (317 to 420 AD) and certainly later, for production of unrefined sugar, with the technique probably coming from the west.

Map showing the spread of sugarcane in Asia, Oceania, and Africa after origin in New Guinea. Map by Obsidian Soul, after a map by Daniels and Menzies, 1996 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

Later expansion (Middle East, North Africa, and Europe)

Sugarcane and sugar milling were introduced to Persia (modern-day Iran) between about 500 and 600 AD. From there, sugarcane growing and sugar production spread to other parts of the Islamic world, including North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Sicily. Irrigation methods were developed to water the sugarcane crop in relatively dry environments, and elaborate sugar mills and refineries were constructed that used water to move the grinding stones that crushed the sugarcane to extract the juice. Conical pots for separating sugar from molasses first appeared.

Slavery, particularly the enslavement of people from Africa, has a long history in the cultivation of sugarcane and the production of sugar. During the Medieval Abbasid Caliphate (750 to 1258, geographically spanning the Middle East and the northern coast of Africa), enslaved people were forced to grow sugarcane in former marshlands located in southern parts of the modern nations of Iraq and Iran. People from East Africa were taken captive and enslaved to prepare the marshlands in this region for cultivation and to perform forced agricultural labor. Enslaved people who worked in the marshlands toiled under very harsh conditions, which, in the 800s, led them to rise up during a protracted revolt called the Zanj Rebellion.

Sugar works at Ghor al-Safi (Zoara) in Jordan. Sugar is thought to have been produced in this area from the 700s or 800s to the 1300s. Photo by Bashar Tabbah (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image resized).

Sugar production was introduced to Christian Europe during the Crusades (the late 1000s to the late 1200s), when Christian forces invaded Islamic lands along the eastern Mediterranean and briefly held territory there. Sugar was often treated as a luxury spice or sweetener in Europe, and, like other spices from the tropics, was a precious commodity. Christian Europe first produced sugar in the eastern Mediterranean Crusader States, which the Crusaders at least partially occupied until the late 1200s, when they were fully driven out.

In the late 1200s, sugarcane production by Christian European powers moved to islands in the Mediterranean, beginning with Cyprus. On Cyprus, some of the labor force was made up of enslaved laborers who were taken captive during war and some was forced labor done by people who were not enslaved. Sugarcane growing and sugar milling were also undertaken on Crete, Rhodes, Sicily and other islands.

In Medieval times, large-scale sugar production was limited by the narrow climatic requirements of the crop (sugarcane only grows above certain temperatures and requires relatively large amounts of water), the fact that sugarcane tends to deplete nutrients from soils, the intense labor required to plant, harvest, and process the canes, and the need for large supplies of wood to make the fires used to evaporate the liquid from the sugarcane juice. It was only later that bagasse, the remains of sugarcane stalks from which the juice has been extracted, began to be used as a fuel, and other efficiencies (like vacuum pans) were developed.

Sugar mill at Kolossi Castle on the island of Cyprus, dating to the mid-1400s. Photo by Chris06 (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Sugar mold, 1500s, Volallonga, Spain. Sugarcane was first brought to southern Spain when it was under Muslim control in the 900s. Sugarcane was grown in Valencia under Christian rule from the 1300s to the 1600s. Photo by Joanbanjo (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Sugarcane in the Americas, 1400s to 1900s

Commercial production of sugarcane exploded after European powers—Britain, Denmark, France, The Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain—started to colonize tropical regions of the world; they used their colonies to produce cash crops, including sugarcane and milled (raw or unrefined) sugar for export. From the 1500s through part of the 1800s, much of the arduous work of growing and processing sugarcane for sugar was done in northern South America, the Caribbean islands, and the Gulf Coast of North America (today, the southeastern U.S.) by enslaved people from Africa and their enslaved descendants.

The beginning: Madeira, São Tomé, and Canary Islands

A major shift in the role of sugar from a rare luxury item to a commonplace sweetener in Europe began to take place in the 1400s. The Portuguese planted sugarcane and established sugar production on Madeira and São Tomé, islands in the Atlantic Ocean off the western coast of Africa. When these islands were colonized by Portugal, they were uninhabited. The Portuguese forced enslaved laborers from Africa to grow sugarcane, particularly on São Tomé. Sugarcane production using enslaved labors also took place on the Spanish-controlled Canary Islands, also off the west coast of Africa. The Canary Islands were inhabited prior to European colonization and were taken by force by Spain; indigenous islanders were enslaved to grow sugarcane and process sugar.

Satellite image of the Island of Madeira, August 2016. Photo by Sentinel-2 L1C + Enhanced Markuse's Wildfire Script, Monja Šebela (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license).

A levada, a type of elevated irrigation channel, on Madeira. The first levadas were built on Madeira (possibly by enslaved people) in part to help irrigate the sugarcane, although they were later used for other crops. Photo by Arian Zwegers (flickr, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, image resized).

First sugar-producing colonies in the Americas

Christopher Columbus brought sugarcane to the Americas in 1493. In the Caribbean, sugarcane growing and sugar milling were first successfully established in the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (the island of Hispaniola, today split between the countries of Haiti, a former French colony, and the Dominican Republic, a former Spanish colony) in the early 1500s. The Spanish brought enslaved people from Africa to grow and process the sugarcane. In the early 1520s, the first revolt of enslaved Africans in the Americas took place in Santo Domingo; it started on a sugarcane plantation owned by Christopher Columbus's son, Diego.

Another early sugarcane growing and milling operation in the Caribbean was started in the colony of Santiago (the island of Jamaica) by Spanish settlers, who forced the indigenous Taíno people to perform the labor of cultivating and processing sugarcane. Spanish sugar production on Jamaica was brief, however, and the sugar industry on the island was only resurrected under British rule more than a century later. In the meantime, the Taíno population on both Jamaica and Hispaniola was decimated by mistreatment at the hands of the Spanish and by diseases introduced by Europeans.

In the early 1500s, Portugal also began growing sugarcane and producing sugar in its South America colony (Brazil), with enslaved African people as its labor force.

Original caption: "Taíno women preparing cassava bread." From La Historia del Mondo Nuovo, 1565, Giorlamo Benzoni (Wikimedia Commons public domain).

Remains of a sugar mill, Engenho dos Erasmos "Ouro Branco," first constructed in 1534 in Sāo Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Rejane Sarmento (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

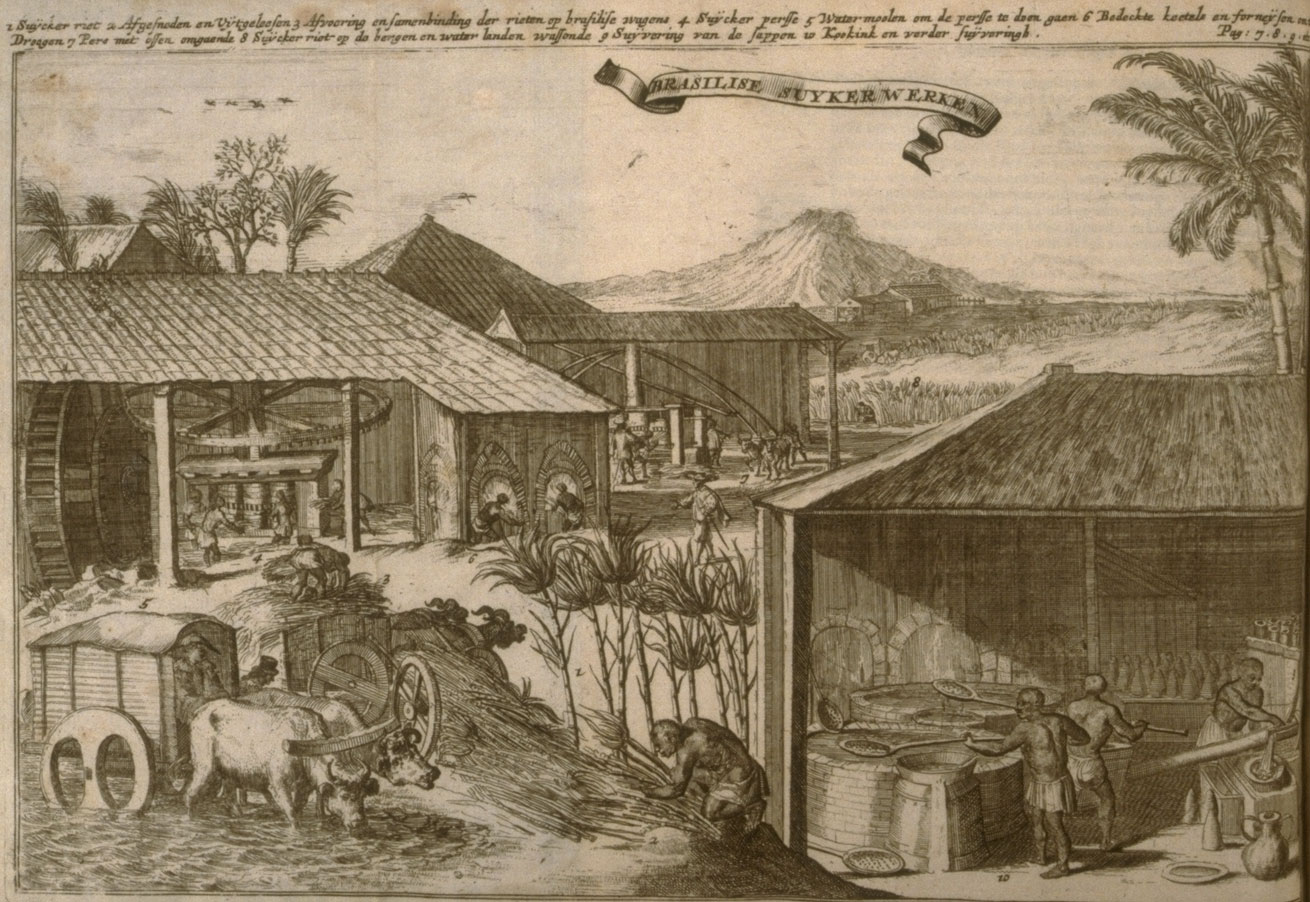

Scenes of sugar milling from Brazil, 1682. From Curieuse aenmerckingen der bysonderste Oost en West-Indische verwonderens-waerdige dingen by Simon de Vries (Slavery Images, public domain).

The Transatlantic Slave Trade

In the Americas, the sugar industry was supported by the transatlantic slave trade, in which people taken captive in Africa were enslaved and brought to the Americas. The international trade in enslaved people from Africa operated from the 1500s to the 1800s, and the majority of the nine to 12 million enslaved people transported from Africa to the Americas were brought to Brazil and the Caribbean, where the climate was suitable for growing cash crops like chocolate, coffee, indigo, and, especially starting in the 1600s, sugarcane. Due to the difficult transatlantic voyage and the hard labor, harsh living conditions, mistreatment by slave holders, and exposure to diseases they encountered upon arrival in the Americas, enslaved people died at a high rate, creating continuous demand for more captives from Africa.

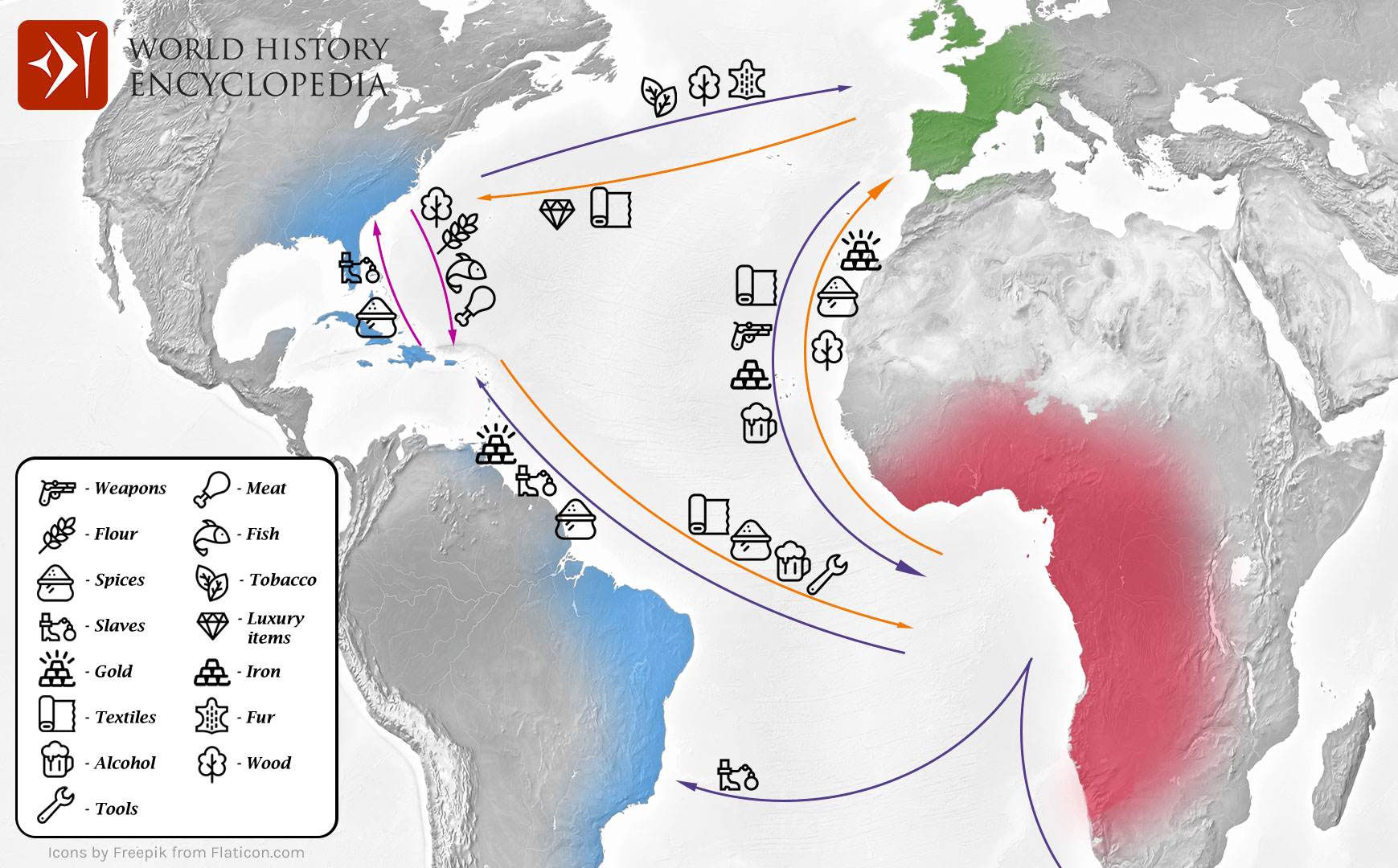

The transatlantic slave trade is sometimes called the Triangle Trade, since it was set up with three sides: One leg brought raw or partially processed goods from the Americas to Europe, one leg brought European trade goods to the west coast of Africa, and one leg brought enslaved African people to the Americas (this is, of course, a simplification, as the system of trading was more complex than this). The international slave trade was banned by Britain in 1807 and by the United States 1808, although slavery persisted in the British Caribbean and the U.S. for decades after that.

Route and extent of the trade in enslaved African people, from the 1500s to the 1900s. Map by KuroNekoNiyah (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

Triangular trade in enslaved people and goods, 1500s to 1800s. Map by Olivier Lalonde (World History Encyclopedia, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 International license).

Slavery in the United States

Beginning in the 1600s, the British colonies that would make up the original U.S. states and territories produced crops like rice and tobacco for export using the work of enslaved African laborers. Cotton, which is most closely associated with slavery in the United States, would only become a major export crop in the late 1700s to 1800s, near the end of the legal transatlantic slave trade to the U.S. (Many enslaved people working on U.S. cotton plantations in the 1800s were thus born in the U.S.)

In the continental United States, only some parts of the region along the Gulf Coast are suitable for growing sugarcane. The sugarcane industry did not fully develop in the U.S. until after the Haitian Revolution, a revolt of enslaved people and free people of color in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti, a country occupying the western portion of the island of Hispaniola, which the French began colonizing in the 1600s) that began in 1791. During this time, some of the white population of Saint-Domingue fled to New Orleans and brought their knowledge of sugarcane cultivation and processing with them. By the 1850s, about a quarter of the world's sugar for trade came from Louisiana. (Cuba and Java were also major nineteenth century producers.) As elsewhere in the Americas, the work of growing and processing sugarcane in Louisiana was done by enslaved people from Africa and their enslaved descendants.

Enslaved women planting tobacco with a white overseer watching over them, Virginia, U.S.A., March 13, 1798. Source: Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Sketchbook, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore (Slavery Images, public domain).

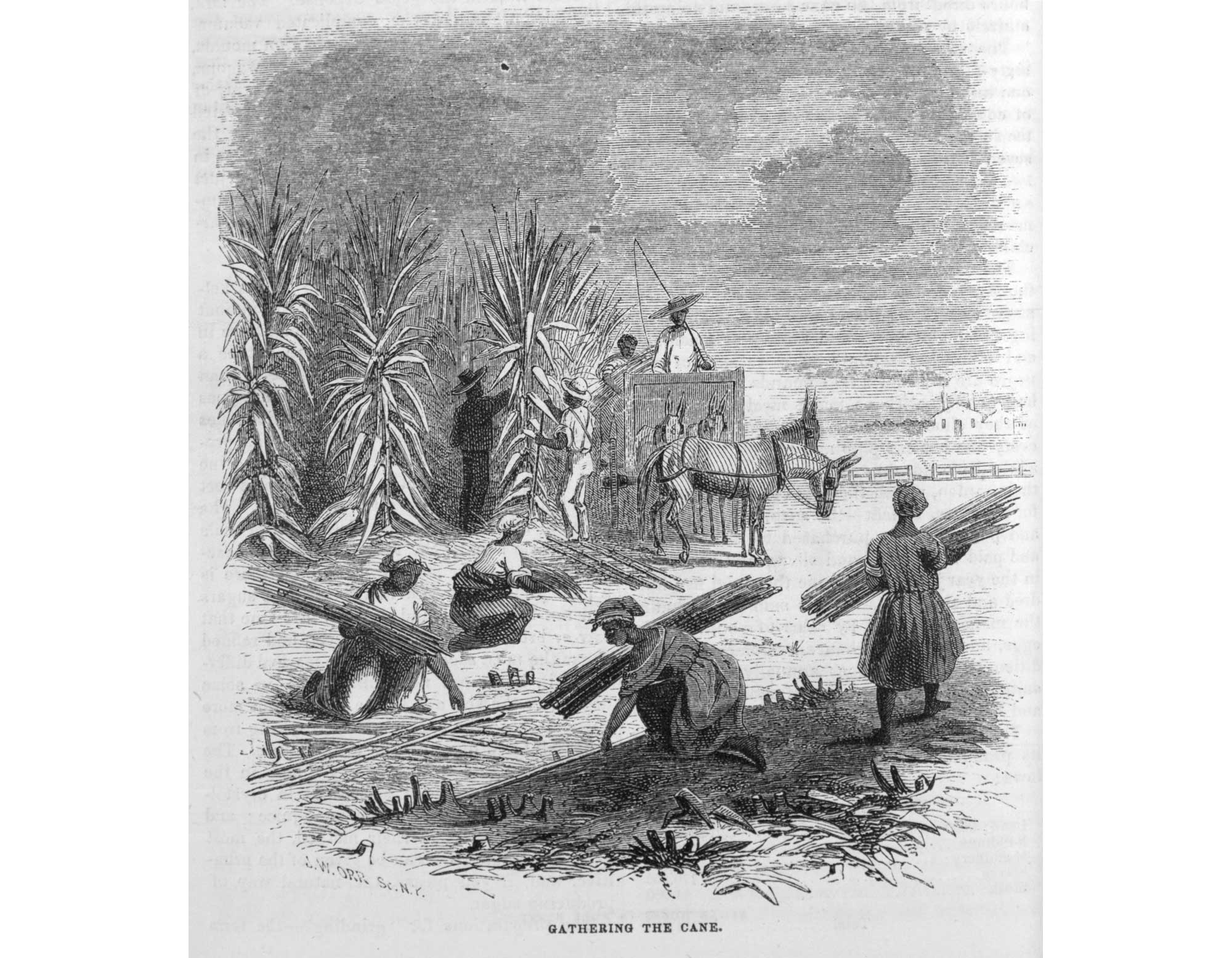

Excerpt from original caption from Slavery Images: "This image shows several enslaved women picking up sugar cane and loading it onto an ox cart in Louisiana [U.S.A.]. The men cut cane before a white overseer with a whip in his hand." Source: Harper's Monthly Magazine vol. 9, pg. 760, 1853 (Slavery Images, public domain).

Sugar production under slavery

Life for an enslaved person working on a sugarcane plantation was notoriously difficult. The owners of sugarcane plantations were generally not concerned about the welfare of enslaved people. Early in the history of sugarcane cultivation in the Americas, enslaved people working on sugarcane plantations died at a high rate and were replaced with newly enslaved people from Africa. The high death rate was a result of the generally brutal conditions under which enslaved people worked and lived, deliberate mistreatment, and diseases and work-related accidents.

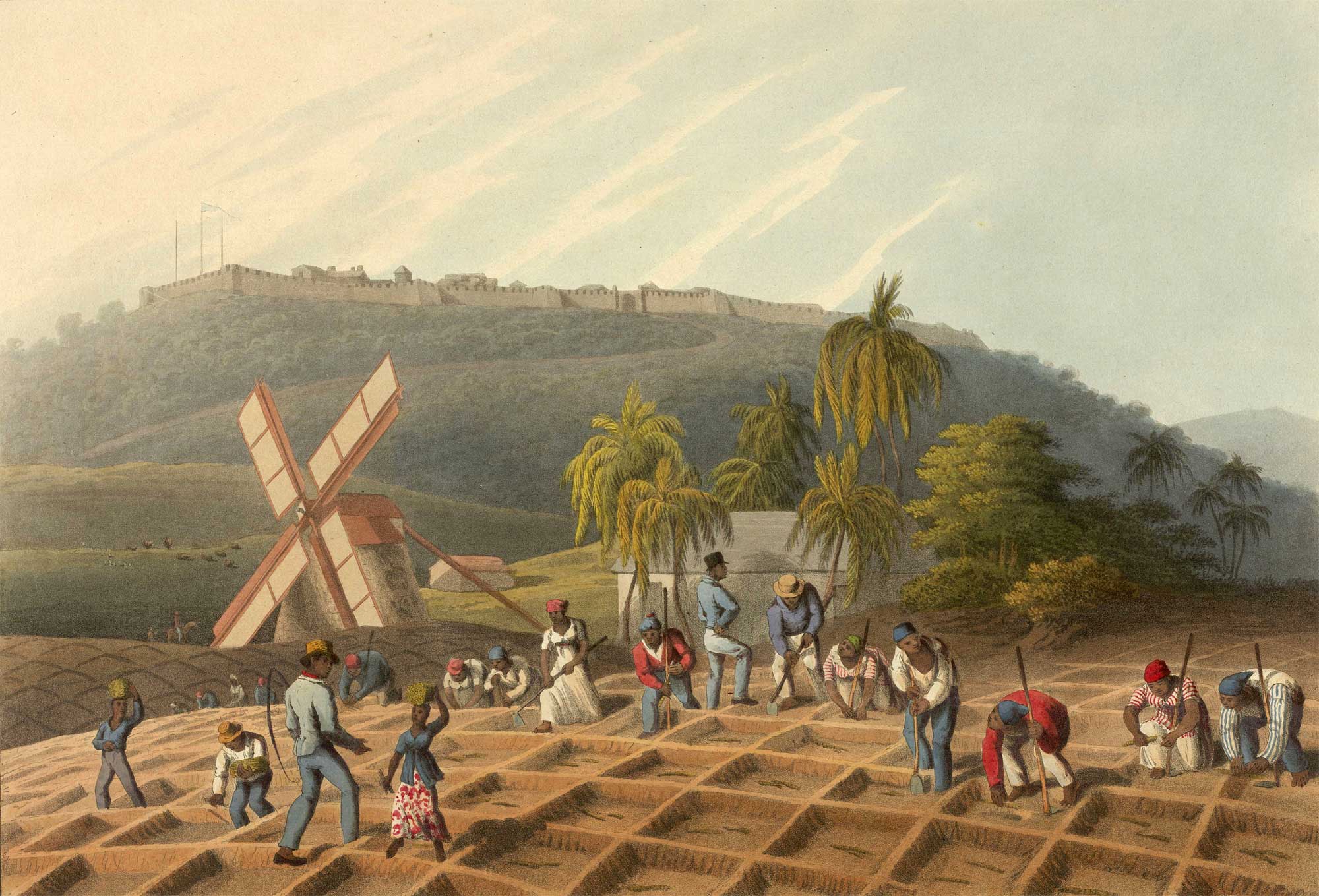

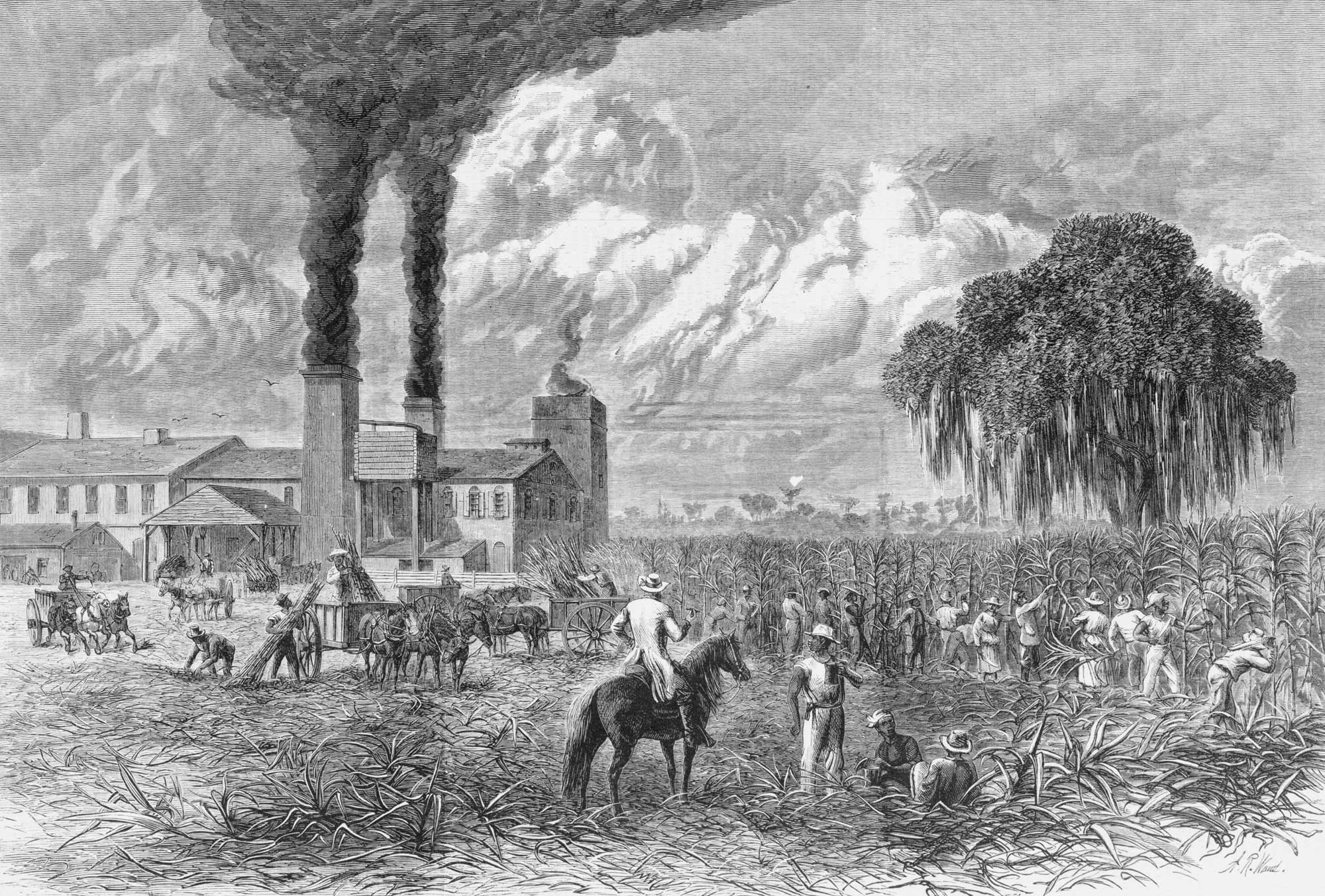

On a sugarcane plantation, enslaved people did the work of growing, harvesting, weeding, and processing sugarcane, often laboring for many hours a day in sweltering conditions. To plant the cane, enslaved people worked in groups using hoes to dig pits or rows in which pieces of sugarcane were planted and then fertilized with manure. At harvest time, they manually cut the canes with curved blades and loaded them onto wagons to be taken to the sugar mill. Their work was supervised by enslaved people called "drivers," who were armed with whips, as well as white men called "overseers."

Enslaved people planting sugarcane in Antigua. The people have dug a series of square pits are are laying pieces of sugarcane in them. One or two enslaved drivers oversee the work. In the background, a person on a horse, probably a white man called an overseer, supervises the planting. A windmill that was used to turn the rollers at the sugar mill can be seen in the background. Art by William Clark (1823), British Library (public domain).

Enslaved people harvesting sugarcane in Jamaica, 1820s. A driver (the man holding what appears to be a long pole) supervises other enslaved people as they cut sugarcane. Art by H.T. De La Beche (Slavery Images, public Domain).

Sugarcane knife or billhook used by enslaved people to harvest sugarcane, Danish West Indies (now the U.S. Virgin Islands), 1800s. Photo by The National Museum, Denmark (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic license, image cropped and resized).

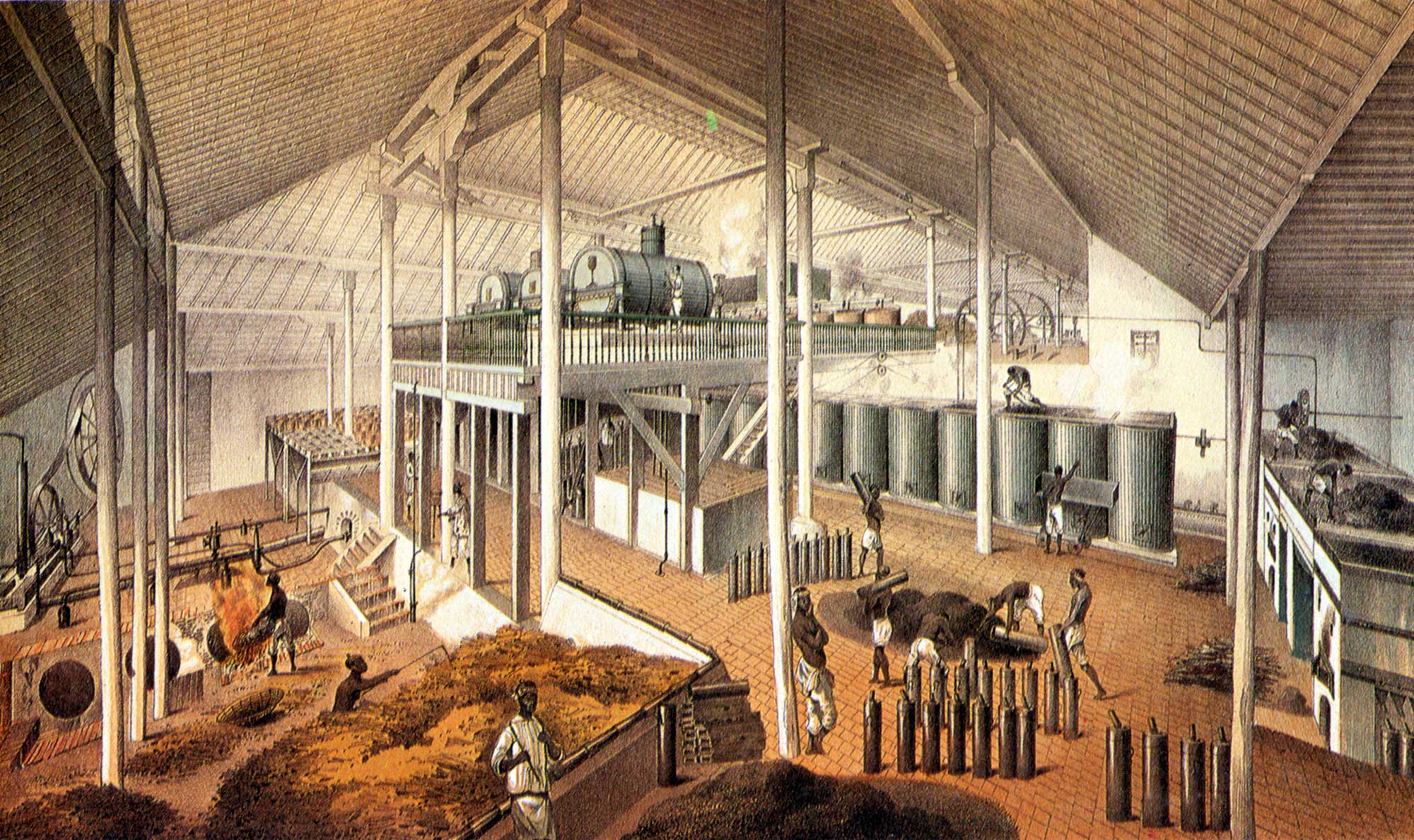

During harvest season, sugar milling went on 24 hours a day six days a week so that the sugarcane juice could be extracted and processed without spoiling. Milling sugar was hot, difficult, and dangerous work. Sugarcane was crushed using vertical rollers and had to be fed into rollers with skill. The people crushing the sugarcane had to move it through the rollers more than once to extract as much juice as possible. If a person feeding sugarcane into the rollers made a mistake and became caught in the rollers, he or she could be pulled in and killed or severely maimed. After the cane was crushed and the juice was collected, it had to be clarified and boiled down in sweltering conditions over open pans. Accidents in the boiling room could cause burns or death.

Enslaved people working in a sugar mill in Surinam, 1831. The illustration shows two people feeding sugarcane into rollers at left; the rollers crush the cane to extract the juice. Note that the rollers are being turned by gears that are powered by flowing water. At center, a person is stoking fires that will be used to heat the extracted juice to make sugar. In the background at right, animals (cattle or mules?) can be seen powering another set of rollers that are used to crush sugarcane. From Voyage à Surinam, description des possessions néerlandaises dans la Guyane by Pierre Jacques Benoit, 1839 (Slavery Images, public domain).

Enslaved people working in a boiling house in Antigua, early 1800s. On the left, enslaved people can be seen boiling cane juice in open pans. The sugar is boiled down in smaller and smaller pans, until it forms massecuite and is transferred to coolers. On the right, white men (possibly overseers) are examining solidifying raw sugar, or muscovado, in the coolers. Art by William Clark (1823), British Library on Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal/Public Domain Dedication).

A boiling house with more modern equipment manned by enslaved laborers in Asunción, Cuba, 1857. On the upper floor, enclosed boilers (vacuum pans or evaporators) concentrate the sugarcane juice; the cylindrical structures on the lower floor are filters that use bone char as a filtering agent. A pile of bagasse burned to heat the sugarcane juice is shown at front, slightly to the left. By Justo German Cantero (Wikimedia Commons, originally from Slavery Images, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license, image cropped and resized).

The sugar industry after slavery

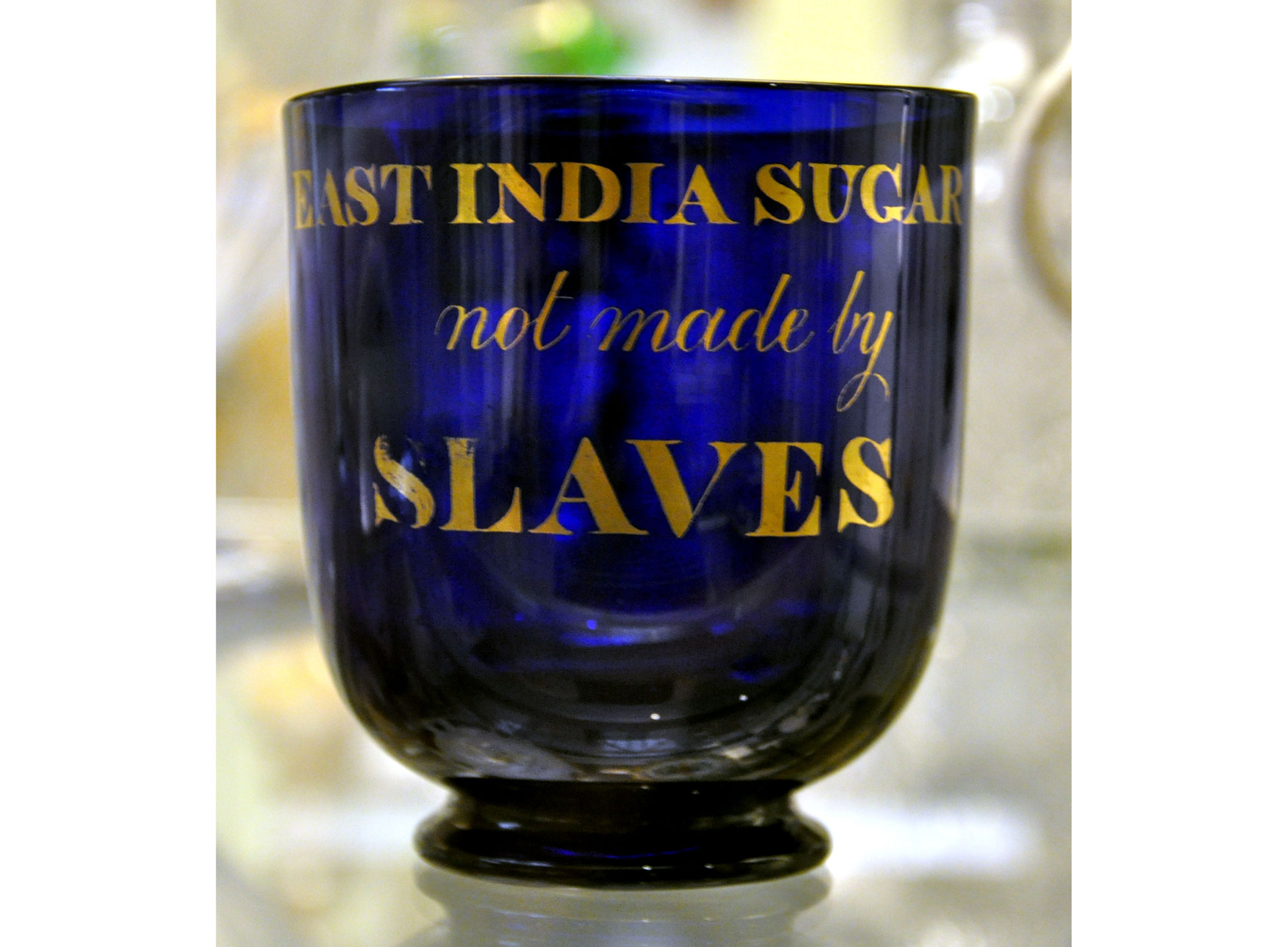

Slavery was slowly abolished throughout the Americas. The deterioration of legal slavery came about due to a combination of political agitation, revolts, and wars that weakened support for slavery and enforced its abolition. Abolitionists agitated against slavery and tried to enlist popular support. Rebellions of enslaved people periodically occurred, like the successful revolution on Saint-Domingue (Haiti) from 1791 to 1804 and the failed 1811 German Coast Slave Uprising in Louisiana.

Slavery was abolished by law in the British colonies in 1838 after an extended period of activism. In the United States, the final abolition of slavery was brought about through the U.S. Civil War (1861 to 1865), a savage conflict that killed hundreds of thousands, and passage of the 13th amendment to the constitution in 1865. Cuba abolished slavery by law in 1886. In Brazil, as of 1822 an independent country, blanket abolition was decreed by law in 1888.

British sugarbowl advertising that the sugar inside was not made using slave labor, 1800s. The abolitionist movement in Britain was successful in convincing many to abstain from using sugar or to buy sugar made in a place that did not use slave labor, although conditions for laborers may still have been abhorrent. The sugar industry in India was controlled by the East India Company and remained relatively small in the 1800s. Photo by Andreas Praefcke (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

After slavery was abolished in various parts of the Americas, the sugar industry continued with a labor force made up of formerly enslaved people, descendants of the enslaved, and immigrants who arrived as contract laborers or indentured servants, particularly from Asia.

Technology also transformed sugarcane growing and sugar processing during the 1800s to 1900s, eventually reducing the need for human labor in sugar mills and refineries and also in the fields for planting, weeding, and harvesting. This wave of innovation began before slavery was completely abolished and did not necessary contribute to its abolition.

As sugar mill next to a sugarcane plantation in post-Civil War (post-slavery) Louisiana, U.S.A., 1875. By Alfred R. Waud (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-USZ62-107717, no known restrictions on publication).

People harvesting sugarcane on Barbados, 1914. Photographer unknown, National Museum of World Cultures (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image cropped and resized).

Sugarcane in Indonesia, 1700s to 1900s

The Americas were not the only place where sugarcane cultivation and sugar milling took place under colonial rule. Another important center of sugar production was the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) in Southeast Asia, especially the large island of Java. The sugar industry was particularly important in the 1800s to the early 1900s, when the Dutch colonized the islands.

Dutch colonization and aftermath

By the 1500s, the Chinese had established sugarcane fields and sugar mills in southeastern China and Southeast Asia to produce muscovado. Chinese sugar millers thus were already producing sugar on Java before the Dutch colonized the island. The Dutch first began traveling to Southeast Asia by ship in the late 1500s in order to trade for tropical spices, which were incredibly valuable commodities in Europe at the time. In the early 1600s, the Dutch East India Company established a permanent base in Batavia (now Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia).

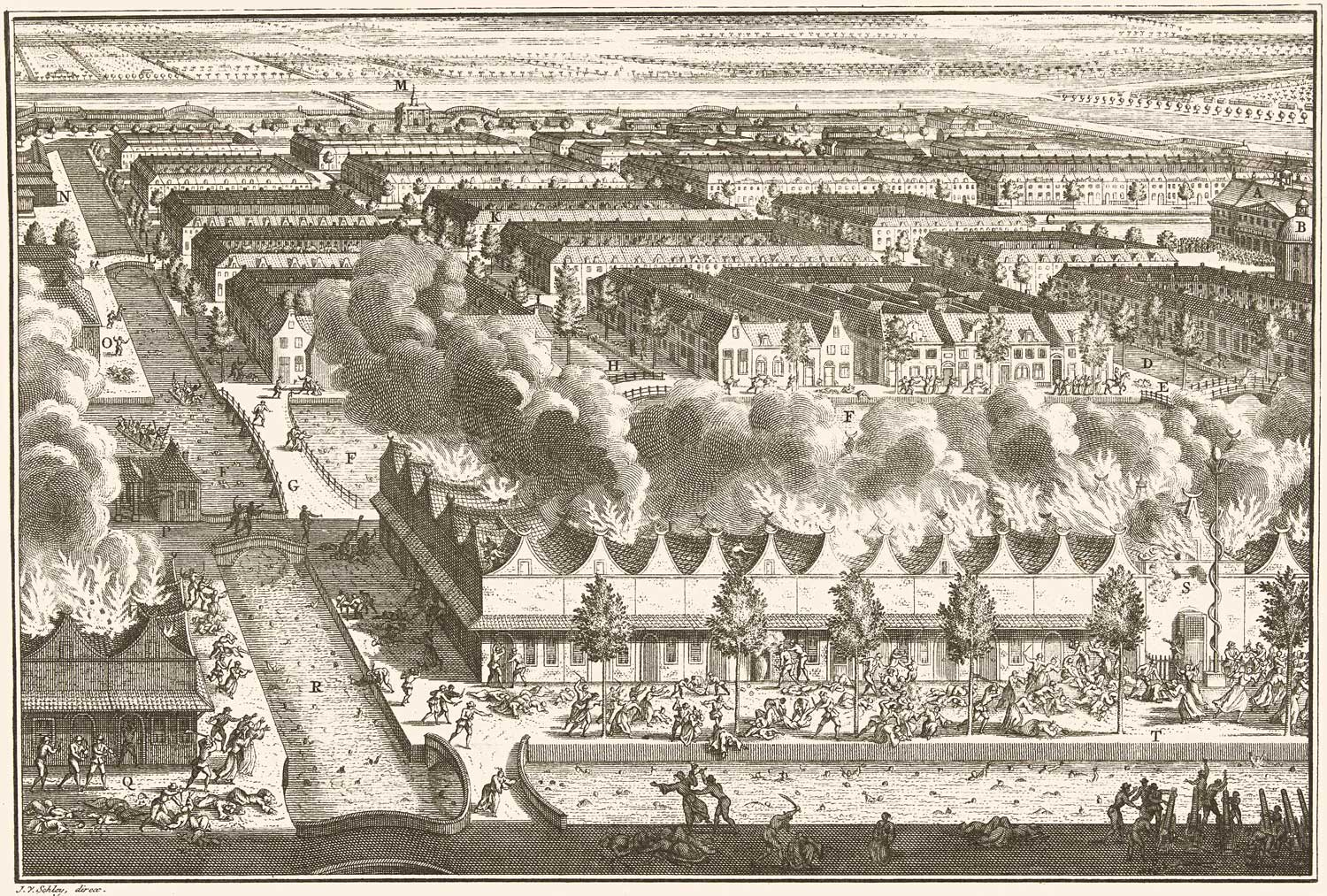

The Dutch did not push Chinese sugar producers out after they first took control of Java. As sugar production ramped up in the Americas under colonial powers, however, the price of sugar fell and work in the sugarcane fields on Java dried up. The Dutch also wished to control more profit from the sugar industry. Dutch authorities began deporting Chinese laborers, who rose up, killing about 50 Dutch soldiers. During the ensuing Batavia Massacre of October 1740, an estimated 10,000 ethnic Chinese people living on Java were massacred by Dutch and local people. The massacre started under the guise of enforcing a curfew placed on Chinese residents to prevent more violence.

Houses of ethnic Chinese people in Batavia (Jakarta) were set on fire during the Batavia Massacre of 1740, Java. Art by Jakob van der Schley after Adolf van der Laan (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Sugar production on Java, late 1700s to 1900s

Eventually, the Dutch encouraged the rejuvenation of sugar production on Java with the help of Chinese sugar millers. From the 1830s to the 1870s, sugarcane in the Dutch East Indies was grown following the "Dutch Cultivation System." Under this system, indigenous people on Java were forced to produce cash crops like sugarcane for export. Sugar was also milled using forced labor in more than 90 sugar mills on the island of Java.

After the Dutch Cultivation System was legally abolished, sugarcane cultivation and sugar milling continued into the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the early 1900s, more than 180 sugar mills existed on Java. For a time, Java was the world's second most important sugar producer after Cuba. Nevertheless, the Javan sugar industry collapsed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Dutch colonial rule ended in the 1940s. Today, Indonesia still produces sugarcane, but is not within the top five countries growing the crop.

Pangka sugar refinery on Java, about 1865 to 1872. Art by Abraham Salm (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

People preparing a sugarcane field for planting in East Java, 1921. Photo by Ohannes Kurkdijian (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

People harvesting sugarcane for the Nieuw Tersana sugar company, Cheribon, Java, between about 1890 and 1911. Photo by O. Kurkdijian (Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

Industrialization and plant breeding on Java, 1800s and 1900s

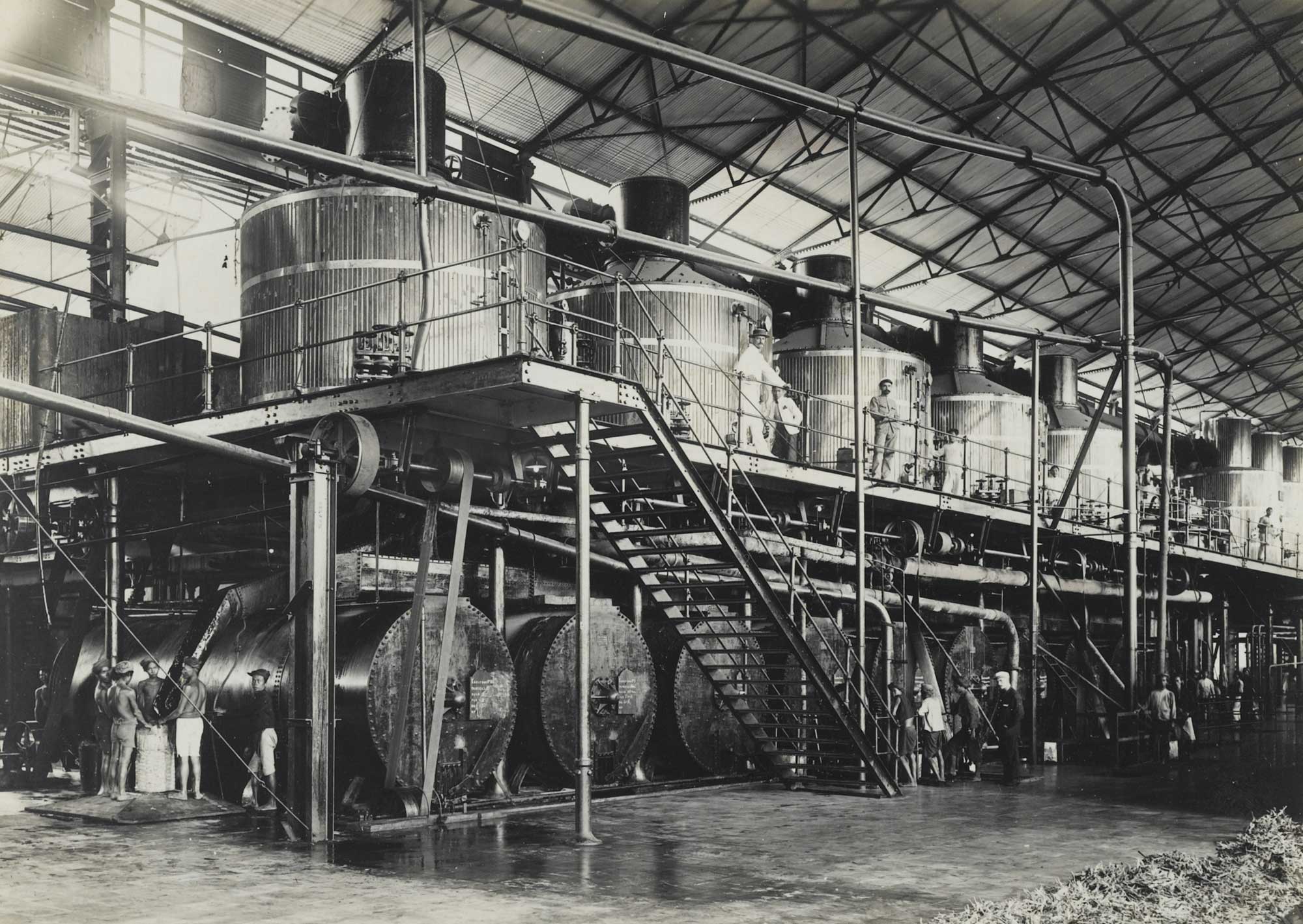

During the 1800s and 1900s, two important innovations helped transform the sugar industry on Java. One of these was the modernization of sugar mills and refineries. Sugar millers on Java were early adopters of vacuum pans in which sugarcane juice was evaporated in enclosed containers under low pressure. Furthermore, centrifugals were introduced to spin the molasses out of sugar, a much quicker and more effective process than allowing molasses to drip out of solidified sugarloaves.

Dutch plant breeders also worked on creating improved sugarcane varieties by cross-breeding different types of noble canes (Saccharum officianarum) and also by cross-breeding noble canes and wild sugarcanes (Saccharum spontaneum). The sugarcane breeding program was spurred by a viral disease that affected 'Black Cheribon', the main variety of sugarcane cultivated on Java since the mid-1800s. In the 1920s, a disease-resistant and sugar-rich cane variety called POJ 2878 was created. POJ 2878 is an important ancestor to modern sugarcane varieties.

Vacuum pans at the Klampok sugar mill, Java, around 1915. Photographer not identified (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

Vacuum pans at the Djatiwangi sugar mill, Indramajoe, Java, around 1940. Photographer not identified (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image cropped).

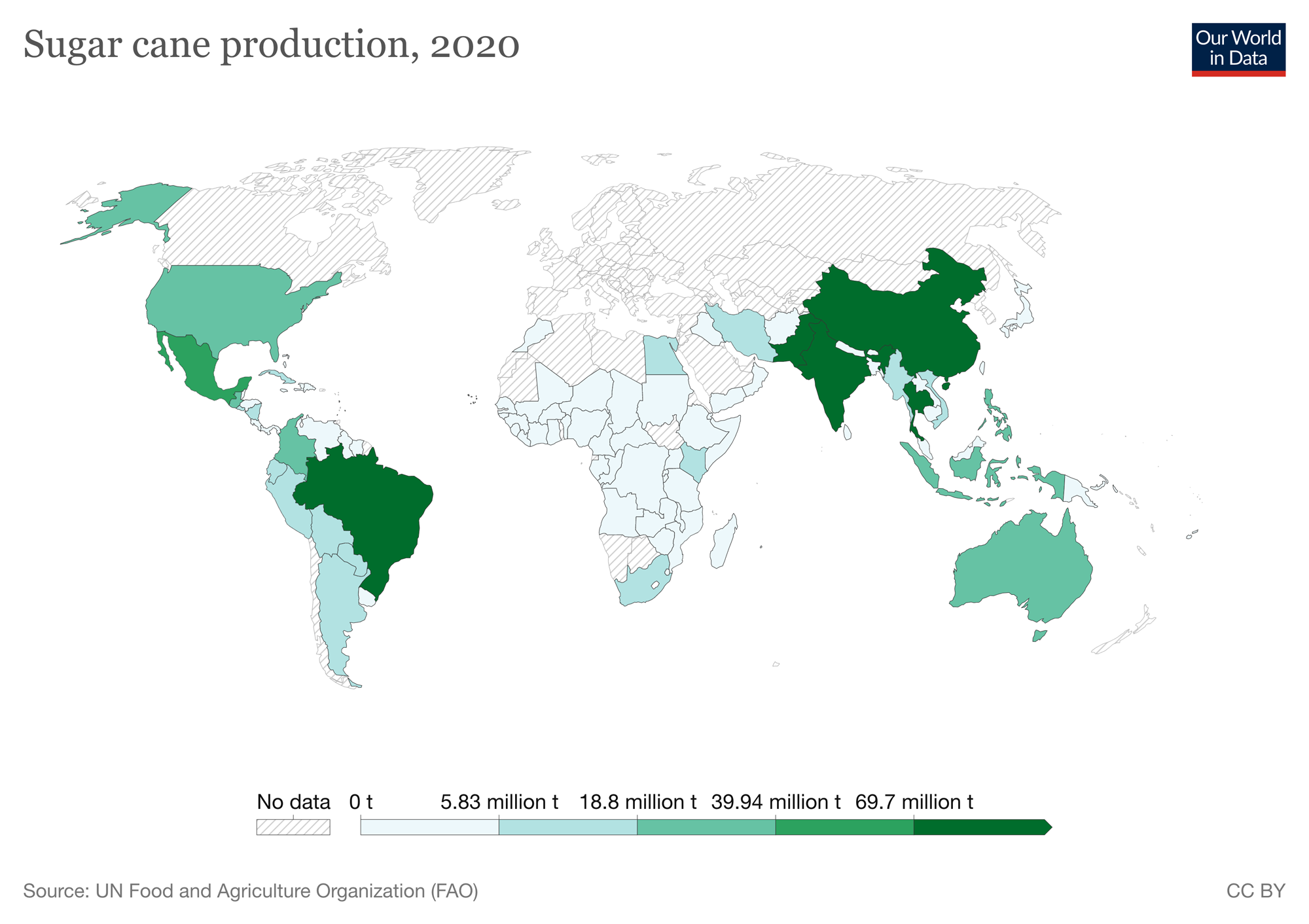

Sugarcane production today

Today, the landscape of sugarcane has shifted somewhat. Brazil, traditionally one of the world's major producers, is by far the top producer of sugarcane today. India, which was not a major sugar-making country in the early 1800s, is today the second-highest producer, far surpassing the third most important sugarcane producer, China. In 2021, Pakistan, Thailand, and Mexico rounded out the top five countries for sugarcane, with Indonesia, Australia, the United States, Guatemala, and the Philippines rounding out the top ten.

The sugar industry in Cuba, which was a major sugar producer in the past, has declined precipitously since the collapse of the Soviet Union around 1990, although Cuba is still the top producer in the West Indies. The Dominican Republic is the second-highest producer in the West Indies, with other islands and countries producing relatively small amounts.

World map of sugarcane production in 2020 by country. Map from Our World in Data (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, image resized).

Sugarcane harvesting, Piracicaba, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Photo by Mariordo/Mario Roberto Duran Ortiz (Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license, image resized).

Resources

Websites

The archaeology of slavery (National Museums Liverpool): https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/archaeologyofslavery/introduction-archaeology-of-slavery

Duruka (Anne Ewbank, Gastro Obscura): https://www.atlasobscura.com/foods/duruka-fiji-asparagus

Madeira ruled the sugar trade (Portuguese Historical Museum): https://portuguesemuseum.org/?page_id=1808&category=3&exhibit=&event=184

Norbert Rillieux and a revolution in sugar processing (American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks): http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/norbertrillieux.html

Slavery in Brazil (The Wilson Center): https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/slavery-brazil

Slavery Images: A visual record of the African slave trade and slave life in the early African Diaspora: http://slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/page/welcome

Slavery in America [U.S.A.] (History.com): https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery

The Haitian Revolution Timeline (Kona Shen): https://thehaitianrevolution.com/

The story of sugar in five objects (The British Museum): https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/story-sugar-5-objects

The Triangular Trade: The economics of slavery and the New World (American Battlefield Trust): https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/triangular-trade

Trick . . . or treat? How did Medieval people get their sugar fix? (L. Laumonier, Medievalists.net): https://www.medievalists.net/2020/10/medieval-sugar/

Articles

Ali, A. The Zanj Revolt: A slave war in Medieval Iraq. Medievalists.net. https://www.medievalists.net/2019/02/zanj-revolt-slave-war-medieval-iraq/

Brown, C. A. 1933. The origins of sugar manufacture in America. I. A sketch of the history of raw cane-sugar production in America. Journal of Chemical Education 10: 1-23: 323-330. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed010p323

Brown, C. A. 1933. The origins of sugar manufacture in America. II. A sketch of the history of sugar refining in America. Journal of Chemical Education 10: 1-23: 421-427.

Carter, J. 2021. The 1740 Batavia massacre of ethnic Chinese in Java. The China Project, 6 October 2021. https://thechinaproject.com/2021/10/06/the-1740-batavia-massacre-of-ethnic-chinese-in-java/

Chandler, G. 2012. Sugar, please. Aramco World, July/August 2012. https://archive.aramcoworld.com/issue/201204/sugar.please.htm

Galloway, J. H. 2005. The modernization of sugar production in Southeast Asia, 1880-1940. The Geographical Review 95: 1-23.

Greenfield, S. M. 1979. Plantations, sugar cane, and slavery. Historical Reflections 6: 85-119.

Horton, M., P. Langton, and R. A. Bentley. 2015. A history of sugar - the food nobody needs, but everyone craves. The Conversation, 30 October 2015. https://theconversation.com/a-history-of-sugar-the-food-nobody-needs-but-everyone-craves-49823

Muhammad, K. G. 2019. The sugar that saturates the American diet has a barbaric history as the 'white gold' that fueled slavery. The New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/sugar-slave-trade-slavery.html

Phillips, K. 2021. 'Spirit of resistance': marking 500 years since the first slave revolt in the Americas. NBC News, 2 December 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/spirit-resistance-marking-500-years-first-slave-revolt-americas-rcna7455

Pringle, H. 2010. Sugar masters in a New World. Smithsonian Magazine, January 12, 2010. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sugar-masters-in-a-new-world-5212993/

Rönnbäck, K. 2023. Sugar plantation slavery. Oxford Research Encyclopedia, African History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.908

Weldon, N. 2021. The free man of color whose invention revolutionized the sugar industry. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 27 October 2021. https://www.hnoc.org/publications/first-draft/free-man-color-whose-invention-revolutionized-sugar-industry

Scientific articles and books

Babu, K. S. D., V. Janakiraman, H. Palaniswamy, L. Kasirajan, R. Gomathi, and T. R. Ramkumar. 2022. A short review on sugarcane: its domestication, molecular manipulations and future perspectives. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 69: 2623-2643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-022-01430-6

Evans, D. L., and S. V. Joshi. 2020. Origins, history and molecular characterization of creole cane. BioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.29.226852

Moore, P. H., A. H. Paterson, and T. Tew. 2014. Sugarcane: The crop, the plant, and domestication. Pp. 1-17 in P. H. Moore and F. C. Botha (eds.), Sugarcane: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Functional Biology, 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118771280.ch1

Politis, K. D. 2015. The origins of the sugar industry and the transmission of ancient Greek and Medieval Arab science and technology from the Near East to Europe. Proceedings of the International Conference, Athens, 23 May 2015. National and Kapodistriako University of Athens, Greece.

Waqaniu-Rogers, A. 1986. Some observations on duruka, Saccharum edule, in Viti Levu, Fiji. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 95: 475-477. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20706033